Permanent Exhibition

The History of Learning: Opening the Future

The Busan Education History Museum is a special place that

preserves the valuable educational history of our region. It vividly

captures the history of education in Busan from the inception of

modern education to the present. From traditional education in the

late Joseon period to today’s innovative education, Busan’s

educational journey across the ages is the story of growth for us all.

There were efforts to preserve Korean culture during the Japanese

occupation, the passion for learning that never faded even in tent

classrooms during wartime, the challenges of young people striving

for a better future, and the evolution of education in step with

changing times-all demonstrate that “learning” is not simply the

transfer of knowledge but a source of hope and a driving force for

change. Through the permanent exhibition at the Busan Education

History Museum, guests can reminisce about the past, understand

the present, and envision the future of education. We hope that each

visitor will discover their very own special meaning of learning here.

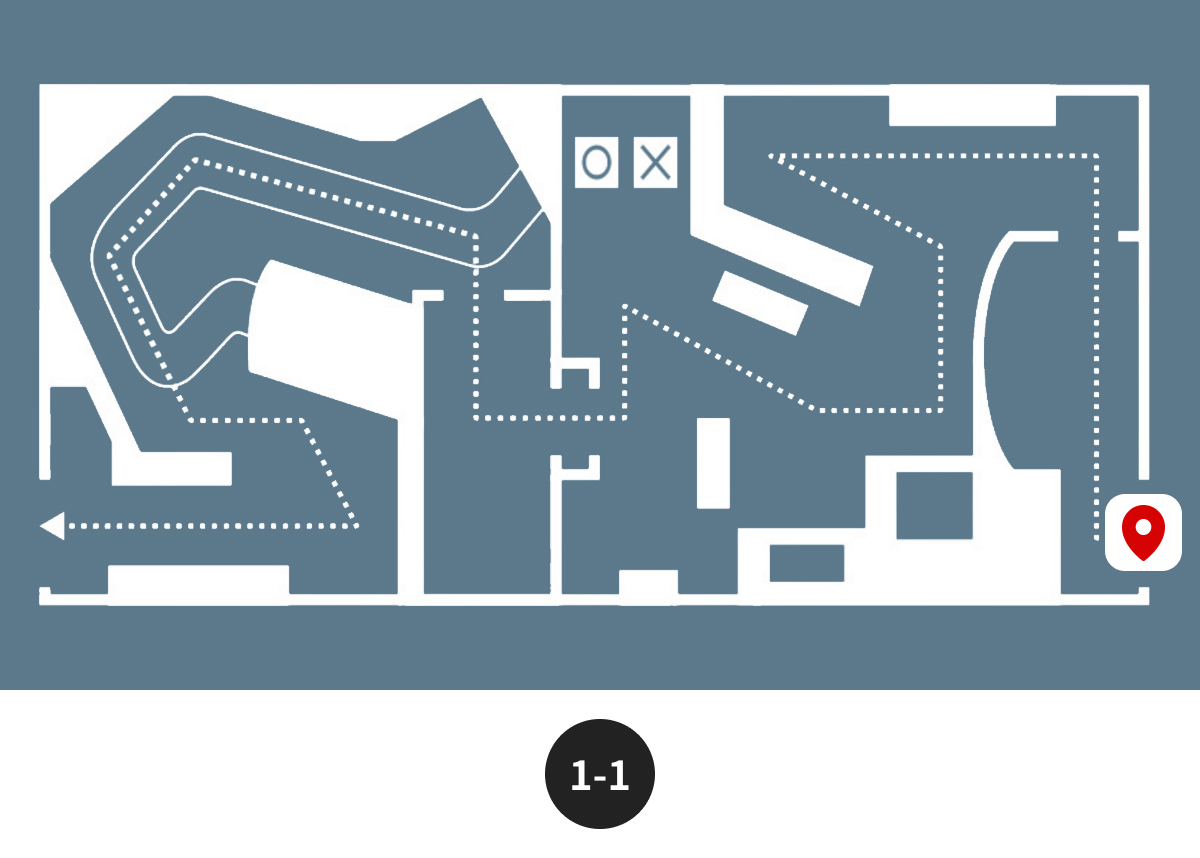

1-1 Education in the Joseon Dynasty

During the Joseon Dynasty, educational institutions were established

across each county and district to spread Confucian values, strengthen

local administration, and promote social stability.

In Busan, educational facilities such as local Confucian schools, private

academies, and village schools were also established, laying the

foundation for the city’s modern education.

With the opening of Busan Port in 1876, modernization began to

transform both society and education. Visionary pioneers in Busan

recognized the need for learning suited to a new era and devoted

their efforts to establishing modern schools. However, following

Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910, the nation entered a difficult

period under colonial rule, when the free use of the Korean language

and script was strictly forbidden.

During the Japanese occupation, despite the loss of national

sovereignty, the people of Busan strove to preserve their cultural and

national identity through education. Students participated in

independence movements both within and beyond their schools, and

even when teaching and learning Korean language and history were

prohibited, their passion for study never waned.

Throughout these challenging times, learning became the hope of the

nation and a driving force that awakened pride. Education was more

than the transmission of knowledge-it was the force that preserved

national identity and kindled the flame of hope for the future.

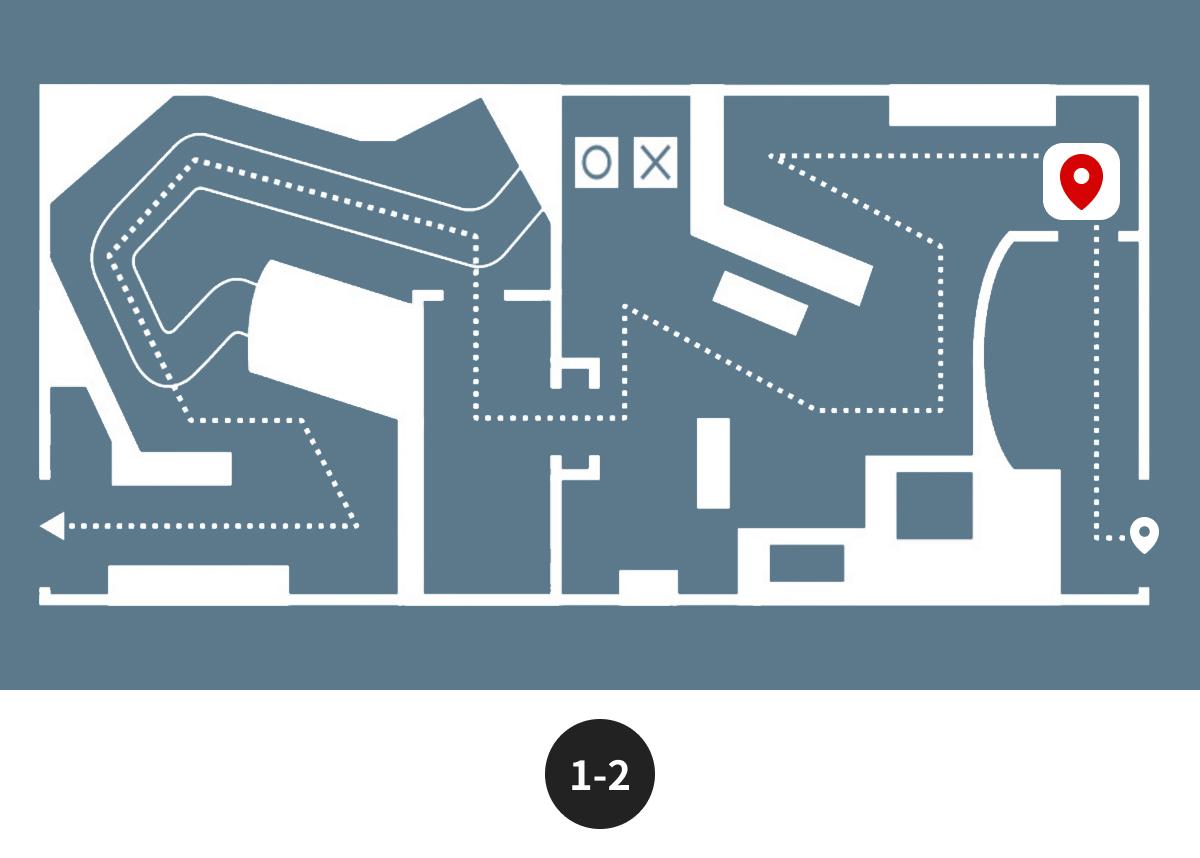

1-2 Educational Structure of the Joseon Dynasty

During the Joseon Dynasty, educational institutions were established in both the capital, Hanyang, and throughout the provinces. Schools were classified as public or private depending on their founding authority. Public institutions included the Royal Academy, Seonggyungwan; the Four District Schools(Sabu Hakdang); and local Confucian schools(hyanggyo). Private institutions included Confucian schools, private academies(seowon), and village schools(seodang). Although educational opportunities were theoretically open to all social classes except the cheonmin, or outcasts, in practice, most students came from nobility(yangban) [sometimes also referred to as the aristocracy].

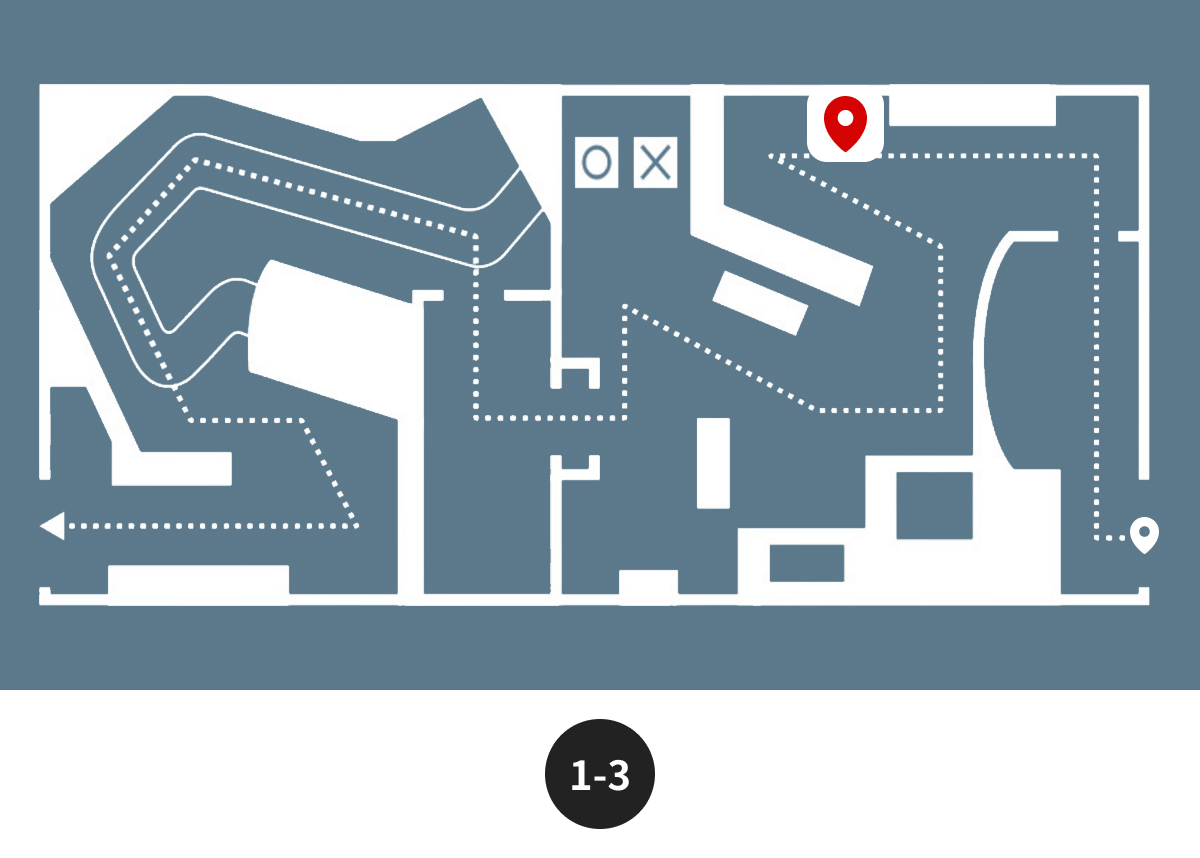

1-3 Seodang(서당, 書堂) - Village School

Seodangs were village study halls established throughout Joseon

communities, serving as neighborhood learning halls. Students learned

reading, writing, and composition through classical texts such as the

Thousand Character Classic (천자문, Cheonjamun, 千字文), Lessons for

the Young (동몽선습, Dongmongseonseup, 童蒙先習), Four-Character

Elementary Learning (사자소학, Sajasohak, 四字小學), Precious Mirror for

Fostering the Mind (명심보감, Myeongsimbogam, 明心寶鑑), and

Vegetable Roots Discourse (채근담, Chaegundam, 菜根譚).

In Busan, examples of seodang included Sisuljae, Samnakjae, and

Yukyeongjae. These schools were attended by children from both the

nobility(yangban)[sometimes also referred to as the aristocracy] and

the commoner families(pyeongmin). Instruction was individualized

according to each student’s level of learning, regardless of age.

Seonggyungwan(성균관, 成均館) - The Royal Academy

The Royal Academy(Seonggyungwan) was the highest educational institution in Joseon and functioned as the national academy. Its purpose was to train scholars and officials equipped with profound Confucian knowledge through both education and research. Students performed ancestral rites to Confucian sages and studied texts such as the Mencius (Maengja, 맹자, 孟子) and the Book of Songs (Sigyeong, 시경, 詩經). Those who passed the preliminary state examinations (sogwa, 소과, 小科) and earned the titles jinsa (진사, 進士) or saengwon (생원, 生員) were admitted to the Seonggyungwan.

Gwageo (과거, 科擧) - The State Examination System

The Gwageo was the state examination system for selecting government officials. It consisted of three stages: the preliminary exam (chosi, 초시, 初試), the secondary exam (boksi, 복시, 覆試), and the final palace exam (jeonsi, 전시, 殿試). From the chosi, 240 candidates were - 3 - selected, and the boksi reduced the number to 33. In the jeonsi, where the king personally posed the questions, the top candidates were ranked into three grades-gapgwa for first to third place, eulgwa for fourth to tenth, and byeonggwa for the remaining successful

Seonbi (선비, 士人) - The Daily Life of a Scholar

The daily routine of a scholar or seonbi, began each day at dawn by dressing neatly and greeting their parents with courtesy before devoting themselves to study. Through constant reading and reflection, they sought to cultivate moral integrity and contribute to a well-ordered society. Their children learned by observing these disciplined habits, developing literacy, culture, and proper conduct through study at the seodang, thus internalizing the moral duties of a virtuous person.

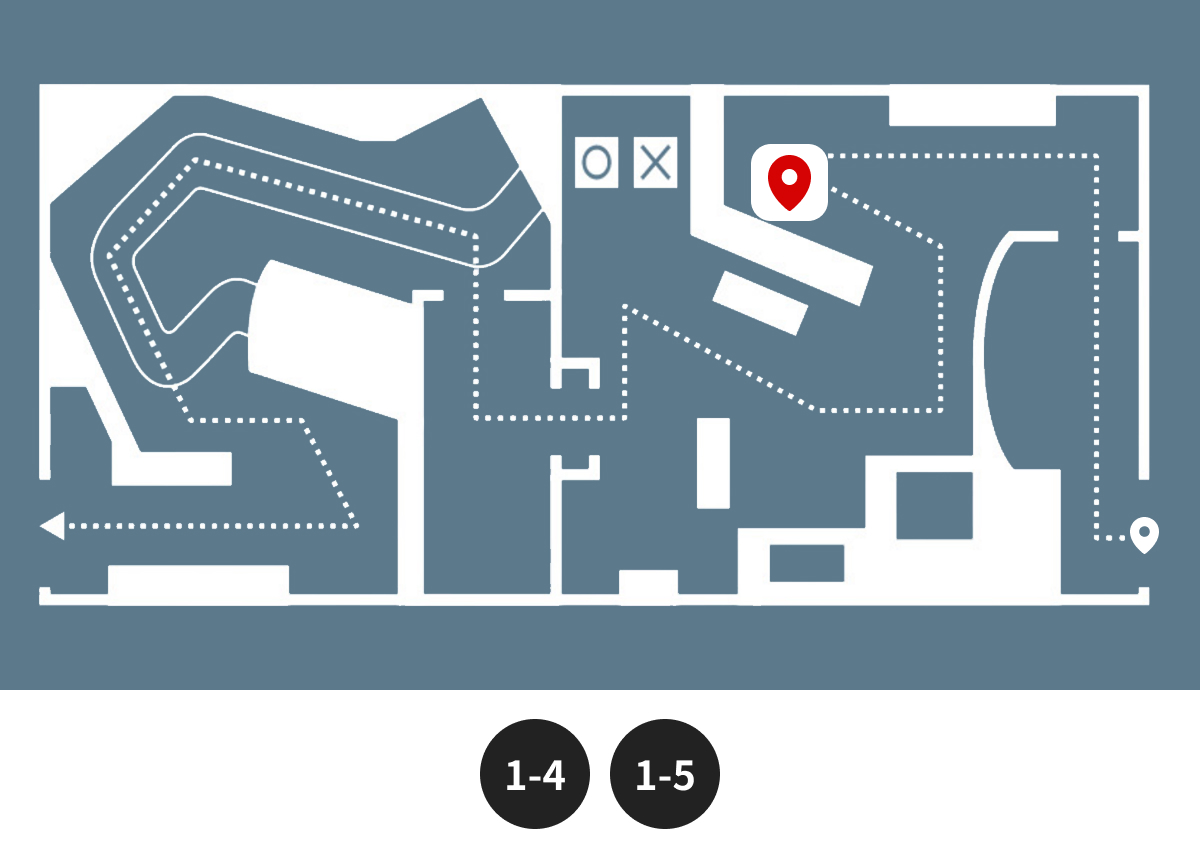

1-4 Cheonjamun (천자문, 千字文) - The Thousand Character Classic

Cheonjamun, or The Thousand Character Classic, was a primer used for beginners learning Classical Chinese. This edition, a woodblock print from the mid-Joseon period, was produced by calligrapher Han Seokbong(한석봉). The book is composed of 250 phrases, each containing four characters, allowing learners to study a total of 1,000 unique Chinese characters without repetition. The content covers a wide range of topics, including moral instruction, general knowledge , history, human relationships, ethics, education, and daily life.

1-5 Dongmongpilsup (동몽필습, 童蒙必習)

Dongmongpilsup, was a textbook used in seodangduring the Joseon Dynasty, created for children who had completed their study of the Thousand Character Classic. The book teaches moral and historical principles through the Five Human Relationships emphasized in Confucianism and through the Hongnon, a section recounting the histories of Korea and China. This lithograph edition dates from the post-liberation period.

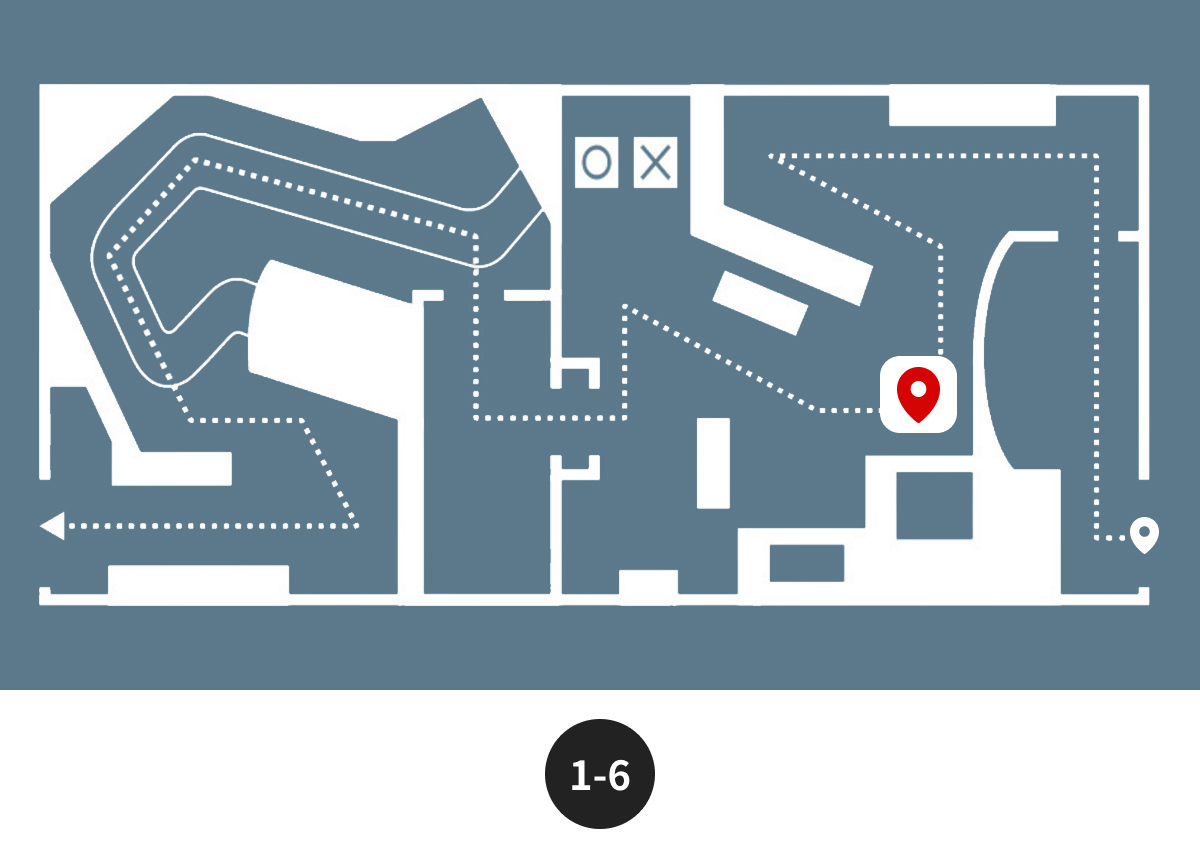

1-6 Encountering Modernity

A nation's prosperity rests upon the enlightenment of its people;

education is, indeed, the foundation for preserving the nation.

In 1895 King Gojong(고종, 高宗) proclaimed the Educational Reform

Edict(Gyoyuk Ip-guk Joseo), launching modern educational reforms to

cultivate talented individuals “healthy in body” (체, che, 體),

“righteous in character” (덕, deok, 德), and “wise in mind” (지, ji, 智)

King emphasized that the path to national strength and prosperity

lay in fostering self-reliance through education.

As interest and aspiration for education grew, modern schools also

began to be established in Busan.

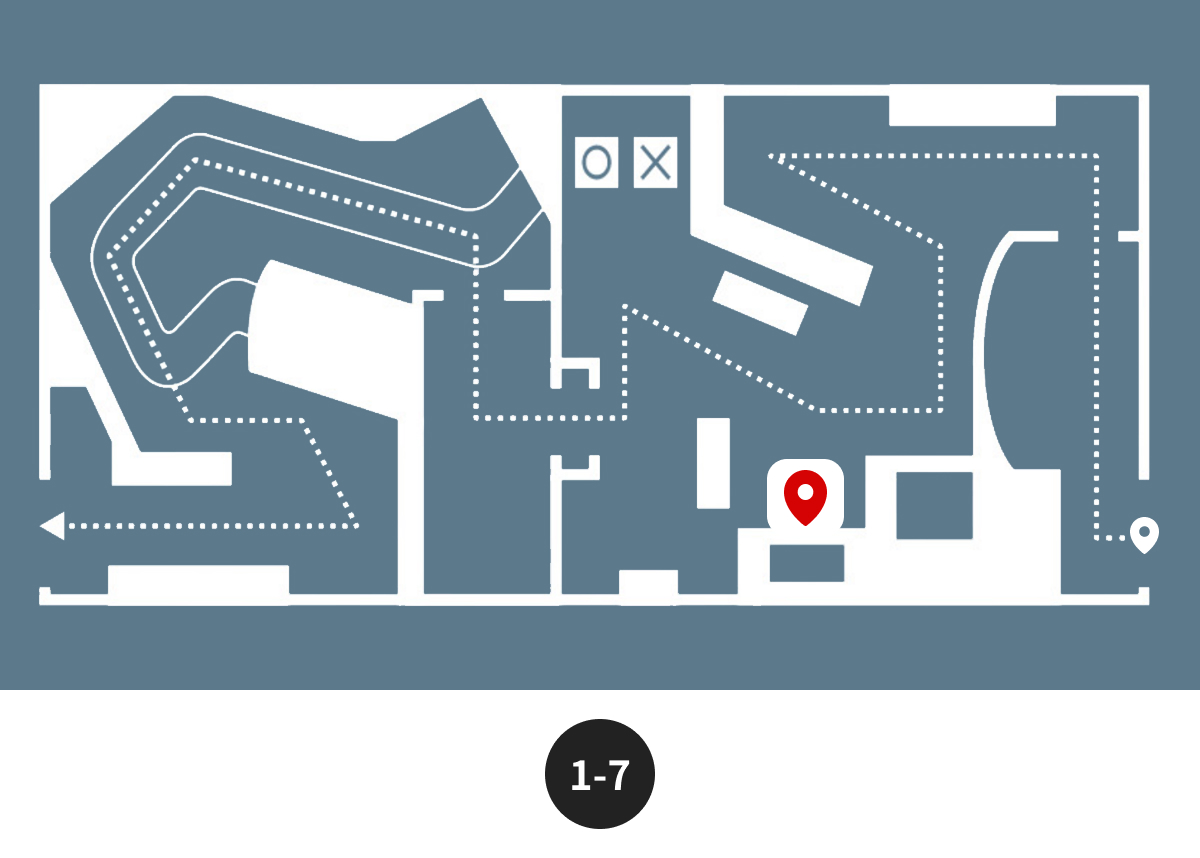

1-7 Founding of Modern Schools in Busan

The rise of modern schools in Busan was not the work of the state

but of forward-looking individuals, religious leaders, and local notables.

Convinced that modern education could forge the talent needed to

weather the nation’s crisis, these founders set up the city’s first modern

classrooms themselves.

To this end, they pooled their private wealth, penny by penny, to

build the schools. The result was a wave of modern private institutions:

Gaeseong School and Ilshin Girls’ School (1895), Dongnaebu School

(1898), Dadaepo Practical School (1902), Myeongjeong School (1906),

Gupo Gungmyeong School (1907), and a number of other private

modern schools emerged.

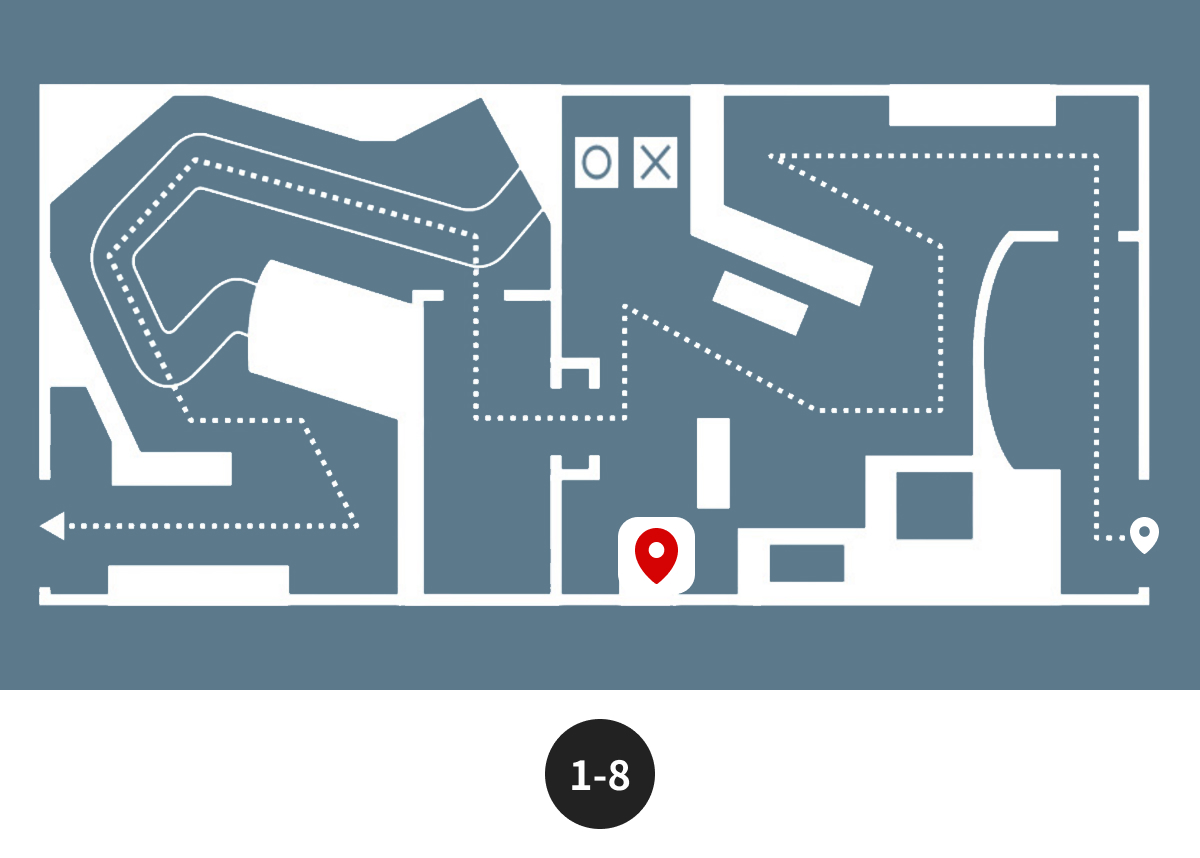

1-8 Students of Modern Universities

Dongraebu School enrolled an average of 40 students each year,

between 1898 and 1903. Most pupils were about 14, though some

were over 20.

Private Kaesung School averaged 60–70 students a year during its

first decade. Most were 16 or 17, but the oldest pupil was 30. A

substantial number of students were dropping out and founding

principal Aranami Heiichirō wrote that the country’s urgent demand

for “new-education” talent sent many teenagers straight into jobs or

overseas to pursue further studies, rather than waiting to graduate.

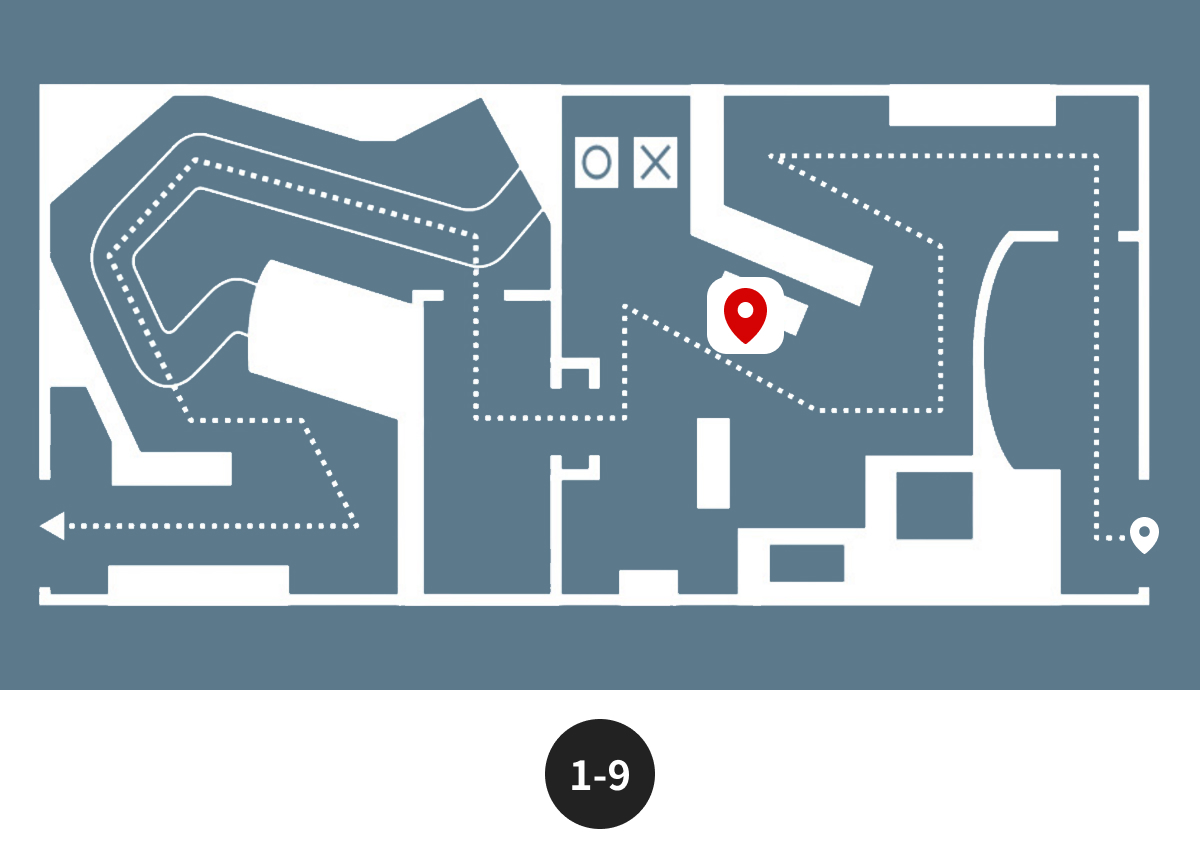

1-9 The Rise of Women’s Educational Institutions

After the Treaty of 1905, Korea’s patriotic enlightenment movement

gathered momentum as part of the struggle to restore national

sovereignty. One of its key ideas was that establishing education

centers for women would strengthen national competitiveness.

Foreign missionaries already in the country built schools that opened

classrooms to women; in Busanjin they founded Ilsin Girls’ School,

the peninsula’s first modern girl’s academy.

The Birth of Private Ilsin Girl’s School

Private Ilsin Girls’ School the first female school in Busan and the

opening venture of the Australian Presbyterian Mission began in

1892, when missionaries B. Menzies and Perry took three orphaned

girls into their Jwacheon-dong home. Intent on training future Korean

missionaries, they started lessons at once; more girls soon gathered. In

1895 the couple opened a day-school, christening it “Ilsin” - “daily

new” - a promise that its rough, tiny start would flourish with each

passing day.

“To elevate a nation, wives and mothers must be educated.”

- B. Menzies

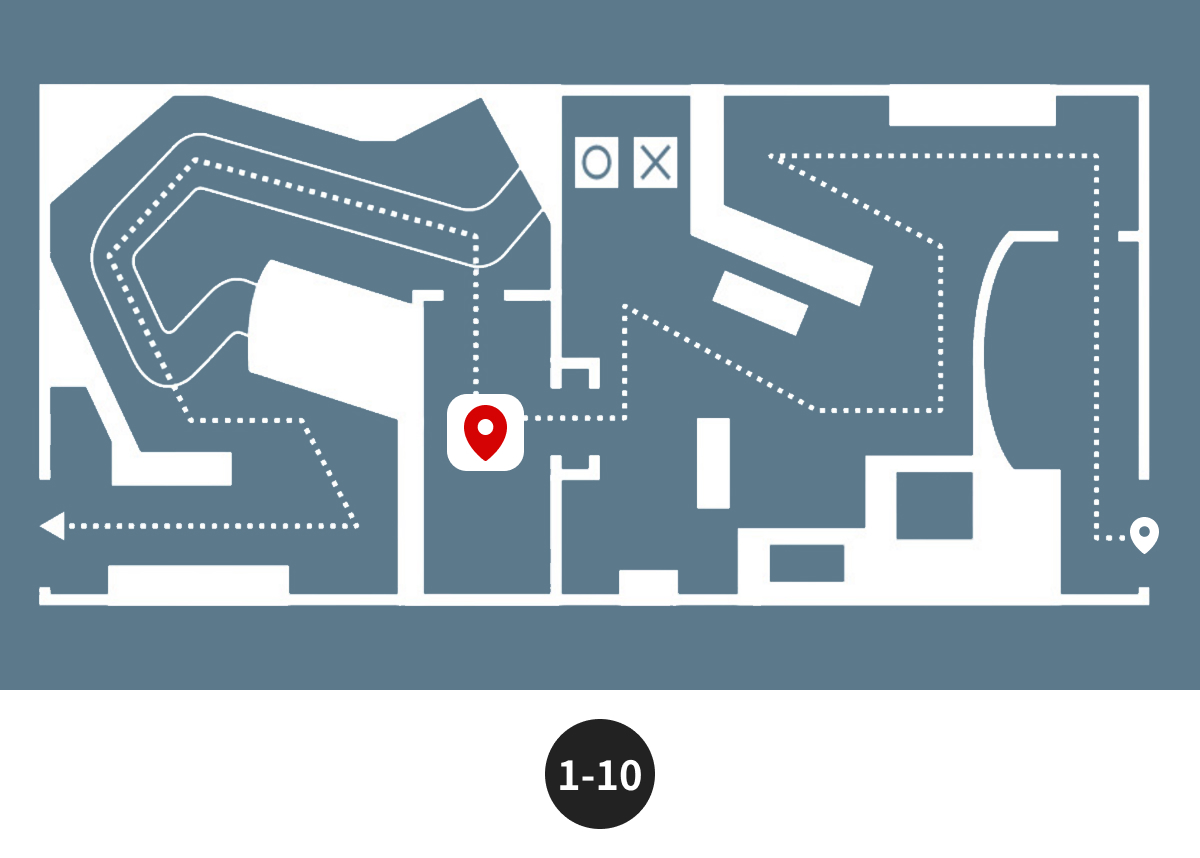

1-10 Resisting through Learning

Here's what this video is about:

After the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty of 1910, Korea lost its

sovereignty, and the Government-General of Korea began in earnest

to establish a colonial education system. The Japanese authorities

revised the ‘Joseon Education Ordinance’ four times, reorganizing

education to suit the ruling policies of each period. Through this,

they revealed their intent to limit Koreans’ learning opportunities and

eradicate/diminish the national spirit.

Despite such oppression, students in Busan strengthened their resolve

for independence and carried out anti-Japanese movements both inside

and outside of school.

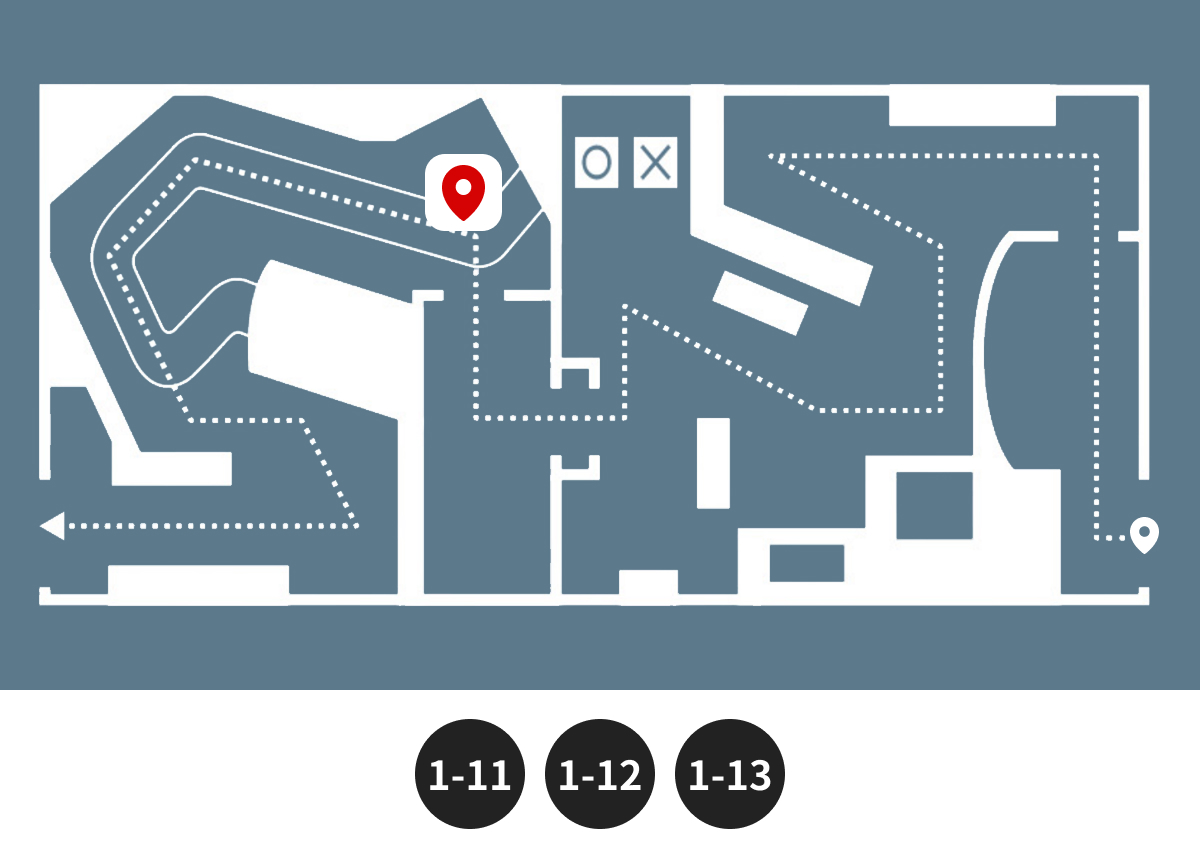

1-11 The Secret Union of Busan Students

On August 22, 1910, the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty was signed.

It was the day when Japan invaded Korea and illegally stripped the

nation of its sovereignty.

In response, students in Busan formed a secret society called

Gusedan(구세단) and led the anti-Japanese national movement.

“I devoted myself to quietly recruiting comrades and met every day

with friends such as Park Jae-hyeok, Kim In-tae, Kim Byeong-tae,

Kim Yeong-ju, Jang Ji-hyeong, and Oh Taek to plan how to spread

the independence movement.”

From the memoirs of Choi Chun-taek (최천택), a member of Gusedan

1-12 가출옥증표 Parole Certificate(1919) Dongnae Educational Foundation

Kim Eung-su (1901–1979, independence activist), a student at Ilsin

Girls’ School, was arrested by the police for taking part in the manse

demonstration on March 11, 1919, in Jwacheon-dong, Busan, while

holding a Taegeukgi. Due to the severe torture she suffered in prison,

her health deteriorated, and she was granted parole from Busan Prison

in August of the same year.

At that time, the police often hurried to release prisoners on parole

when they became critically ill from torture in order to avoid having

them die inside the prison. The crime recorded on her parole certificate

is ‘Violation of the Public Order Act,’ and the sentence length (five

years in prison) is also written there.

1-13 가출옥자여권 Parole Pass(1919) Dongnae Educational Foundation

This is the parole pass of Kim Eung-su (김응수) (1901–1979,

independence activist), a student at Ilsin Girls’ School. Kim was

supposed to be imprisoned until September 27 for her participation in

the manse movement, but she was released on parole on August 17

after her health deteriorated, due to severe torture.

At the time, even when prisoners were paroled while still having time

left on their sentence, they were required to obtain permission from

the Japanese authorities to be issued a parole passport, in order to

travel. This passport states that she would depart on September 15

and arrive in Busanjin on the 16th.

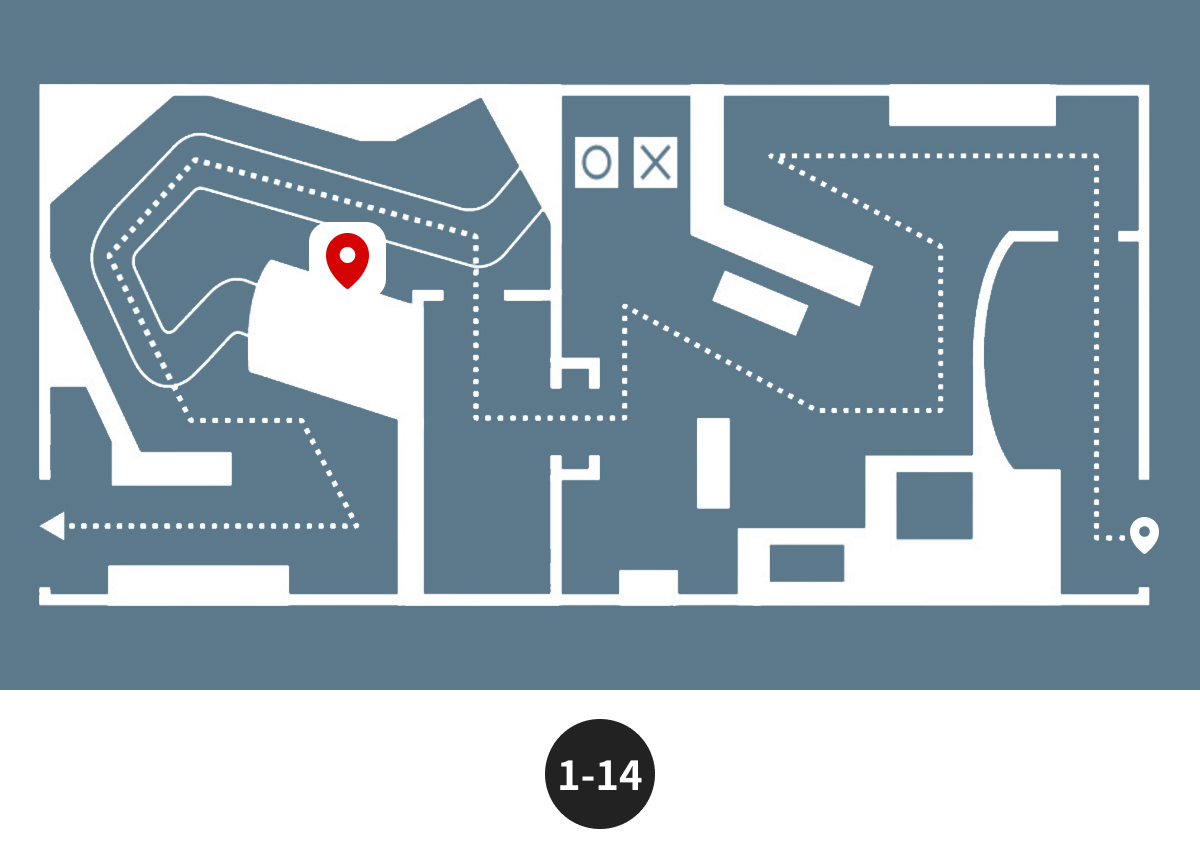

1-14 Changes in Education Before and After the Manse Movement

The Government General of Korea, established by Japan, issued the

In reality, this was an empty policy. It intensified censorship of the

Korean press and weakened the teaching of Korean history and

geography, while strengthening Japanese language education.

Meanwhile, in Busan, as the desire to regain national sovereignty

through education spread, the number of applicants who wished to

enter ordinary primary schools and advance to higher schools increased

significantly, but the number of schools was far from sufficient.

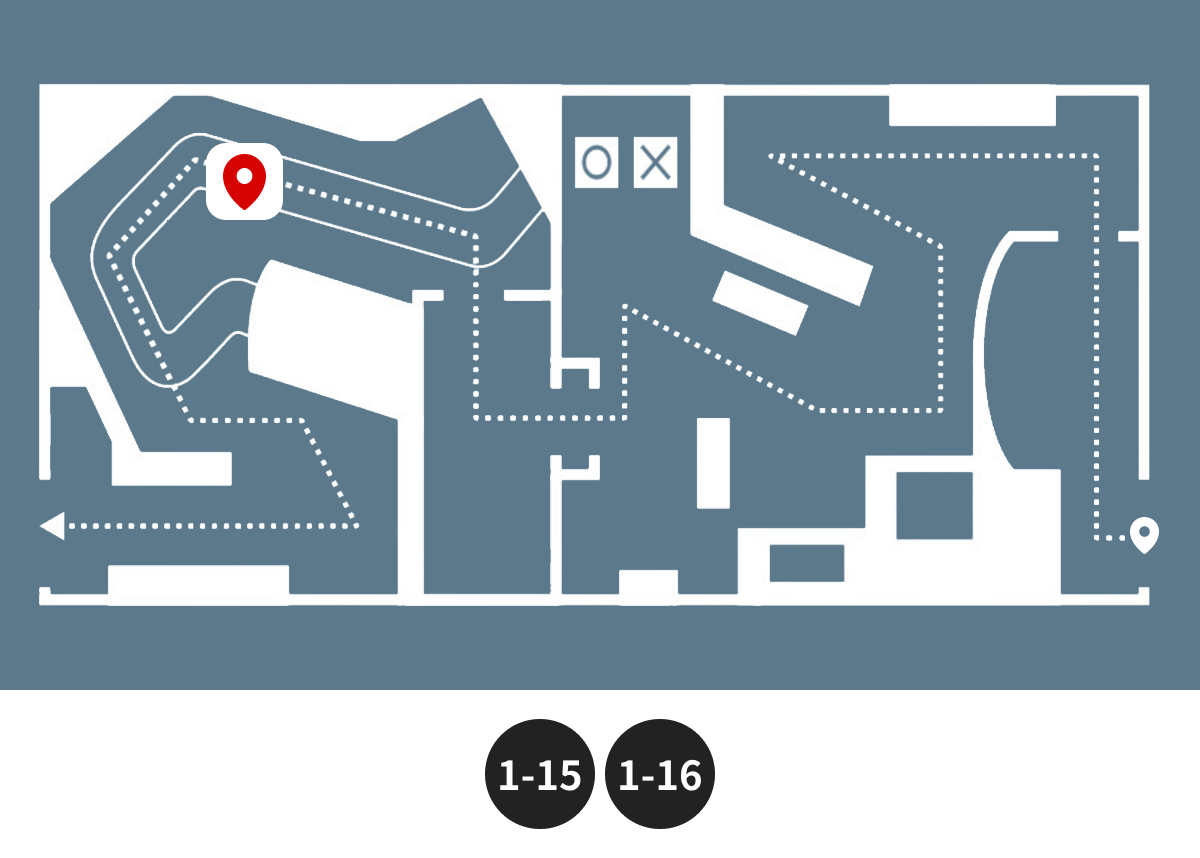

1-15 이인희 학적부 1930년대 School register of Lee In-hui (이인희), National Archives of Korea (History Record Hall)

Lee In-hui (이인희), a fifth-year student at the Second Busan Public Commercial School, participated in the protests, and subsequently was expelled on December 27, 1940.

1-16 중등교육 수신서 권2

Middle School Morals and Ethics Textbook

This is a middle-school–level moral education textbook published by

the Government-General of Korea during the Japanese occupation.

The subject of moral education was one of the central tools used to

cultivate loyal imperial subjects.

Such textbooks began to appear after the Residency-General was

established in 1906. In 1910, all textbooks containing content that

promoted Korean national consciousness were confiscated, and only

those limited to simple ethics and health were exempt from censorship.

Additionally, the Government-General directly compiled and supplied

textbooks in moral education, national language (Japanese), Joseon

language (Korean), classical Chinese, geography, and history, with

the intention of erasing Korean pride and identity.

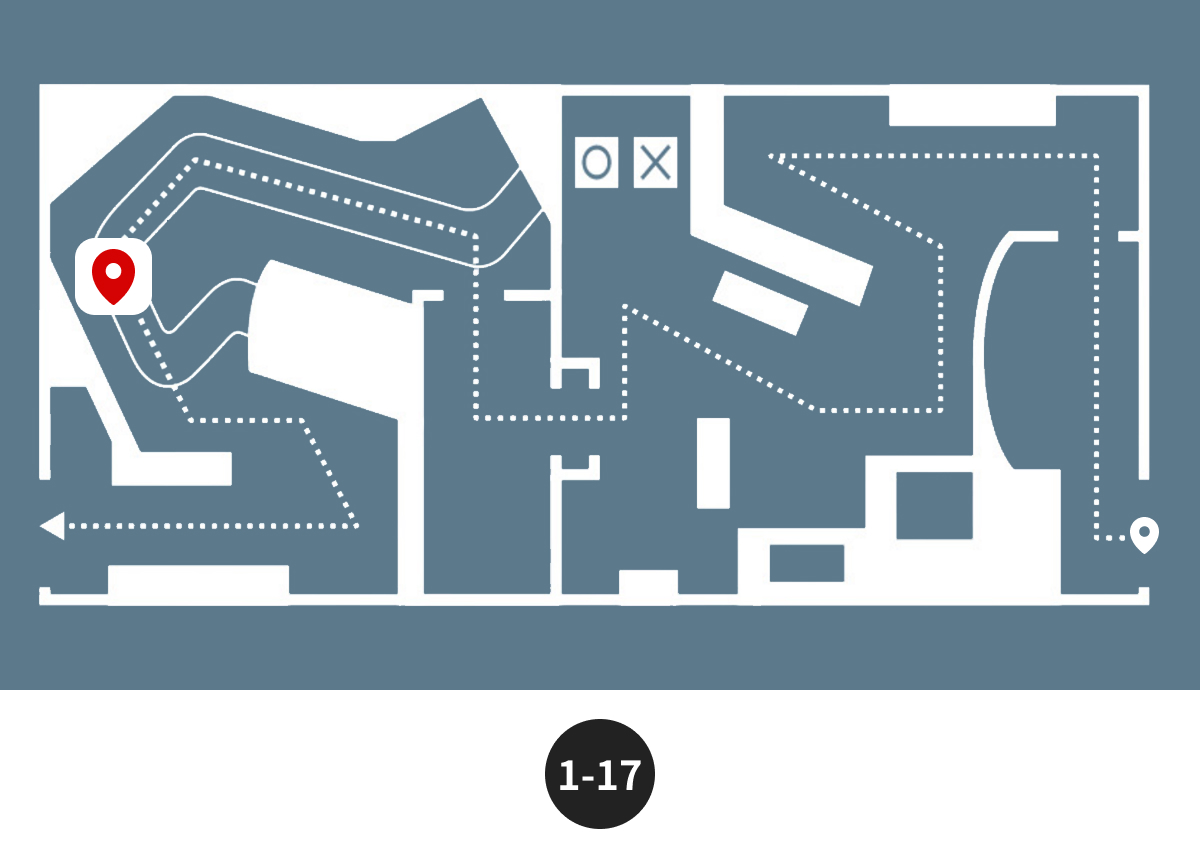

1-17 The Nodai Incident, the Anti-Japanese Student Resistance in Busan

On November 23, 1940, the Second Gyeongnam Student Force

Improvement Defense Games were held at the Busan Public Sports

Field (today’s Gudeok Stadium), with students gathered from Busan,

Masan, Jinju, and other nearby regions.

On November 23, 1940, the Second Gyeongnam Student Force

Improvement Defense Games were held at the Busan Public Sports

Field (today’s Gudeok Stadium), with students gathered from Busan,

Masan, Jinju, and other nearby regions.

During the previous year’s event, Dongnae Middle School (동래중학교),

a Korean school, had clearly won. In the 1940 event, Dongnae Middle

School was again expected to win, but a biased ruling by the judge,

Japanese Army Colonel Nodai (노다이), awarded first place to Busan

Middle School (부산중학교), a Japanese school. Teacher Kim Yeong-geun

(김영근) and the students of Dongnae Middle School protested the

discriminatory ruling. When Nodai dismissed their protest, the students

became enraged.

Students from Dongnae Middle School, the Second Busan Public

Commercial School (now Gaeseong High School), Ipjeong Commercial

School, and Choryang Commercial School left the public sports field,

and started a march through the city, and stormed Nodai’s official

residence. More than 200 students were arrested by police and

military police. Fifteen ringleaders were imprisoned, and others were

disciplined including 21 expelled, 44 suspended, and 10 reprimanded.

One student, Kim Seon-gap (김선갑), died a martyr eight months

after his release due to torture-related injuries. The Nodai Incident

stands as a major student resistance movement carried out under

the wartime regime in the final years of the Japanese occupation.

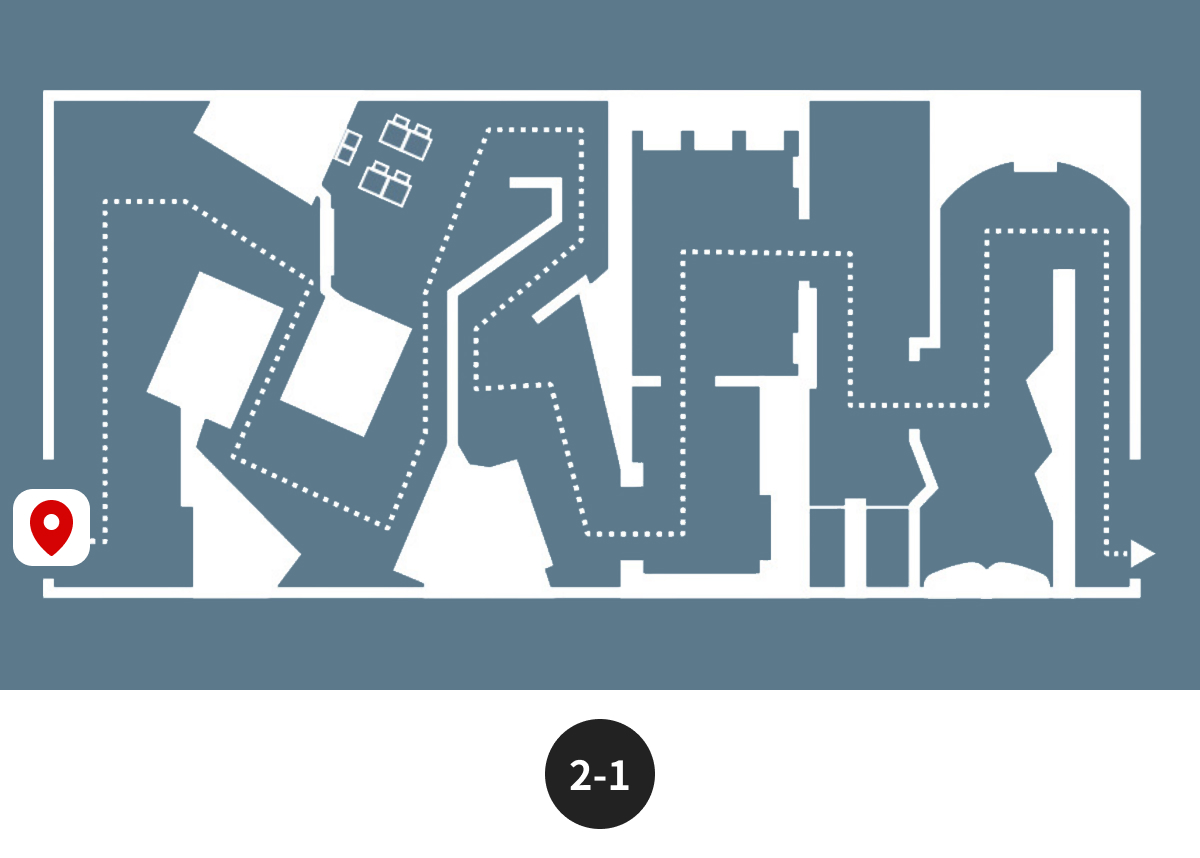

2-1 Learning Continues in Busan, the Wartime Capital

In 1950, just three days after the outbreak of the Korean War, the

capital city of Seoul was captured.

The government designated Daejeon and Daegu as temporary capitals

up to you. However, as the attacks continued, Busan, the final

stronghold, ultimately became the provisional capital.

Busan, where refugees from all across the country gathered, became

the political, economic, and cultural center of the Republic of Korea

for 1,023 days, from August 18, 1950, to July 27, 1953 (excluding the

period during which Seoul was recaptured).

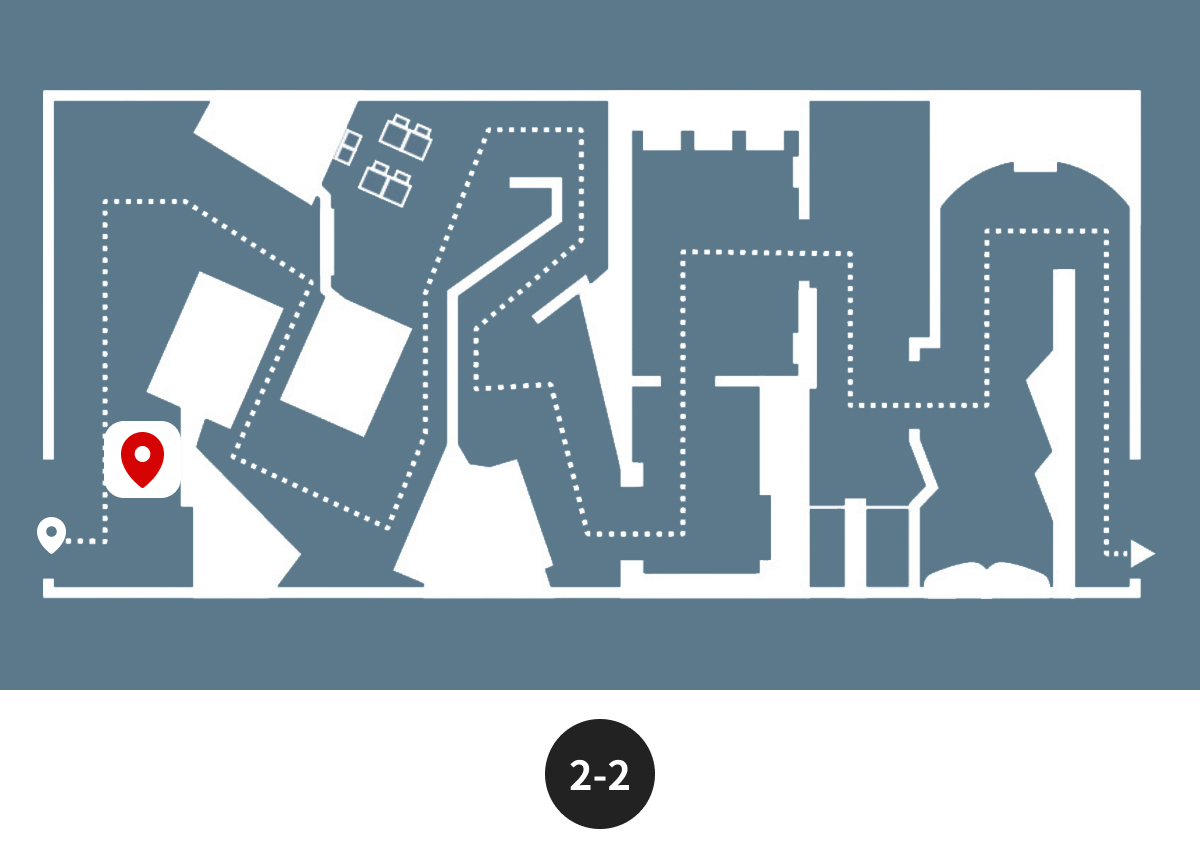

2-2 The Story of Chulsoo(철수), a Refugee

After the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, Busan was filled with refugees. Even during the difficult period of war, Chulsoo(철수) never let go of his studies. Day by day, he held onto his dream and hope of returning to school. Through his diary, we learn the stories of people who did not lose hope, even amid the hardships of war, [because they held on to learning].

철수의 일기 Chulsoo’s Diary

Friday, March 9, 1951

Rumbling, lightning flashes!

At last, we arrived in Busan. [My] father, mother, sister, baby brother,

and I couldn’t get train tickets, so we walked for two long months

with the stream of evacuees. We clapped whenever army vehicles

passed, but shook with fear whenever explosions erupted or shells fell

nearby. How could one nation and one people turn their guns on each

other? Whenever I cried, [my] father gently patted my head and said,

“There will be hope in Busan.”

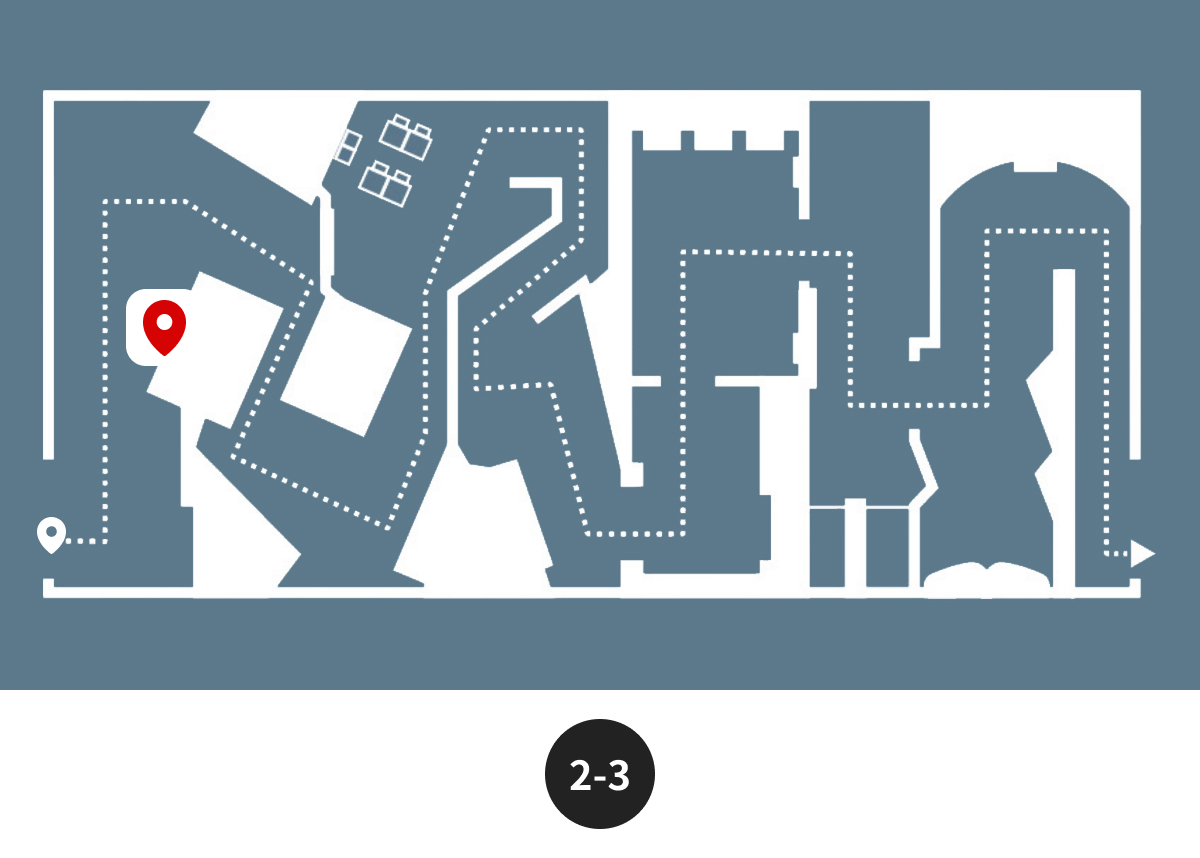

2-3 철수의 일기 Chulsoo’s Diary

Wednesday, March 14, 1951

A house of up and down hope

The first place we went after arriving in Busan was the refugee

camp. It was packed like a bean-sprout sieve, and more people kept

coming, so we could hardly find a space to stay. My father decided

we should go halfway up the mountain and build a small shack.

While my father and mother built it, my sister and I gathered boxes

and sacks near the U.S. military base. My legs hurt from climbing

up and down, but I felt happy thinking that we would finally have a

home.

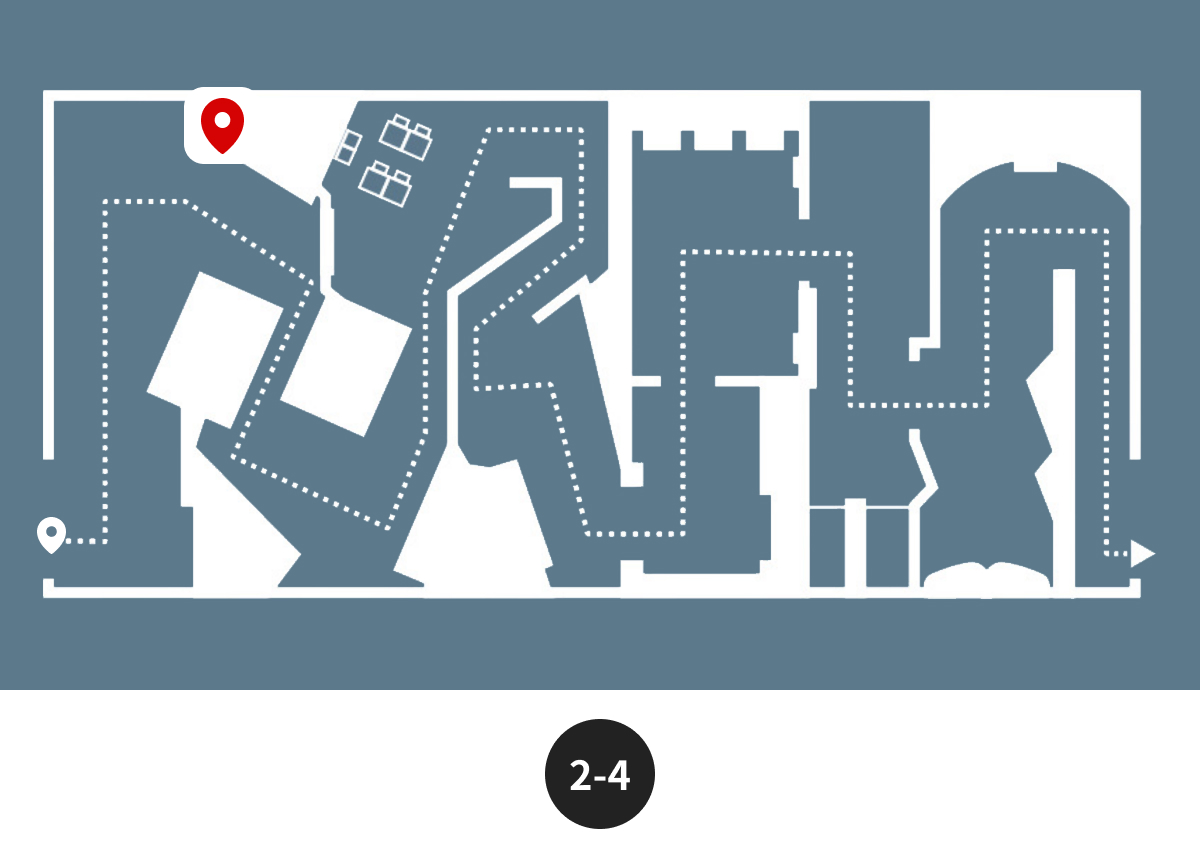

2-4 철수의 일기 Chulsoo’s Diary

Tuesday, October 30, 1951

A star twinkles in the heavy night sky

[My] father works for the U.S. military because he knows a little

English. [My] mother receives supplies from the base and sells them

at the market. I attend tent school, and sister does housework while

looking after [our] younger brother. Once, I nodded off while

studying under the lamp. When [my] father came home late that

night, he told me, “You’re the pillar of this family. You must study

and help rebuild our home.” His words made me feel ashamed. He

added, “If you don’t study hard, you might not even realize when

war breaks out and we have to evacuate. To be the pillar of the

family, you must grow stronger.”

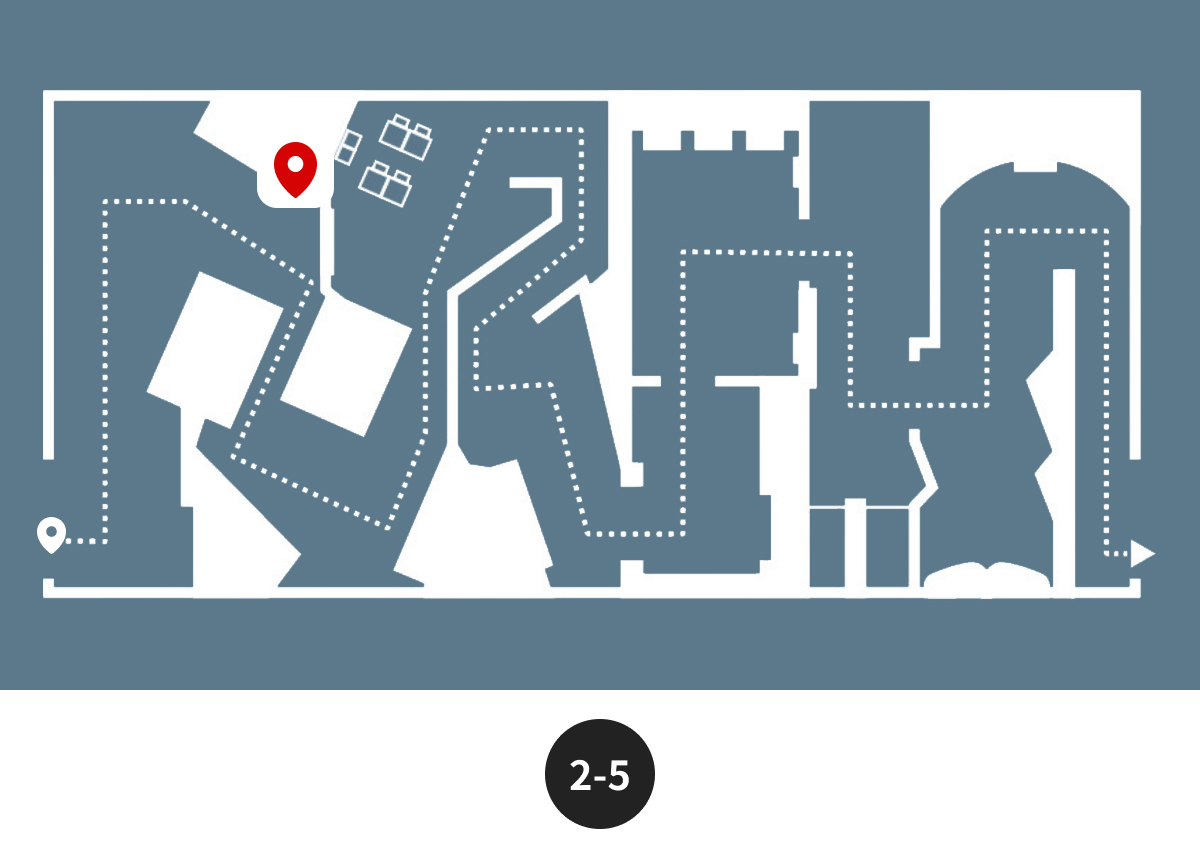

2-5 철수의 일기 Chulsoo’s Diary

Saturday, March 22, 1952

Spring rain falls in the grass

When [my] sister went to school in Seoul, she was a good student.

After we moved to Busan, she couldn’t attend school because she

had to care for [our] brother and help mother. Even so, she never

neglects her studies and reads books on her own. Everyone in our

mountain village praises her for being bright and hard-working. To

me, my smart and kind sister is the most wonderful and admirable

person in the world.

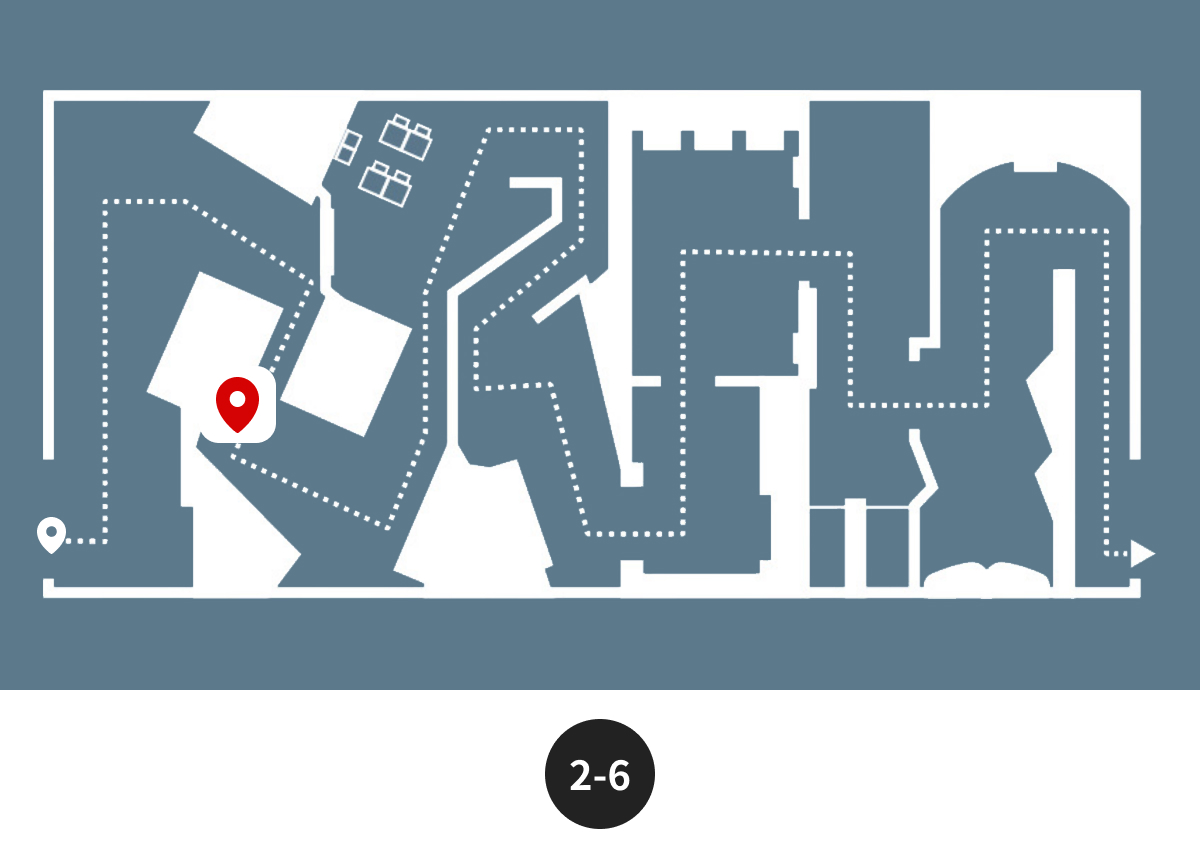

2-6 철수의 일기 Chulsoo’s Diary

Monday, April 23, 1951

The warm moonlight seeps into the house

Sometimes after tent-school class I visit the international market.

[My] mother sets up her stand and sells canned goods, chocolates,

and biscuits. Today, on my way home after stopping by to see her, I

heard a strong voice nearby - a college student teaching English

lessons. When I review what I learn in tent school alone at home,

there are often things I don’t understand. I thought that if I had a

tutor, I could study much better.

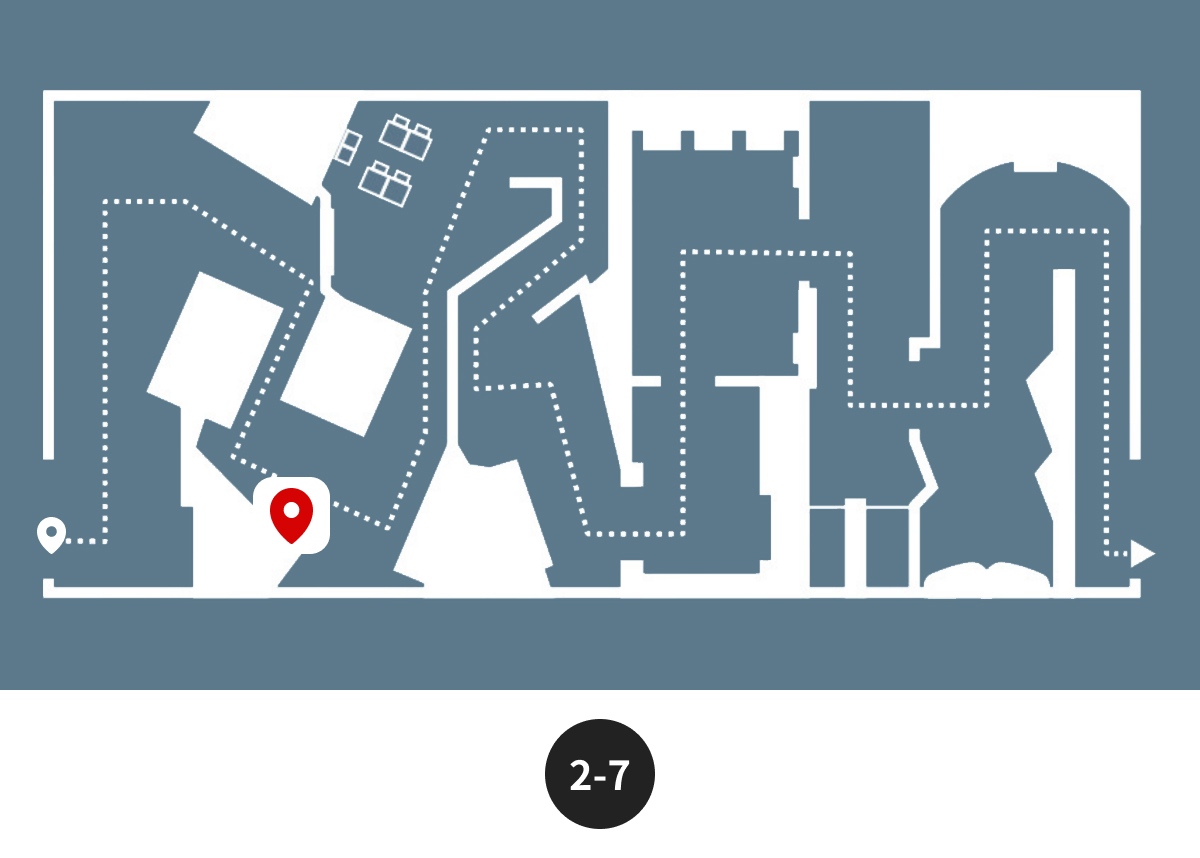

2-7 철수의 일기 Chulsoo’s Diary

Wednesday, May 7, 1952

The quiet rustle of the night when everyone is asleep

Our shack in Busan doesn’t have its own bathroom, so we use the

communal toilet in the village. Last night, after studying late, I grew

sleepy and went there to wake myself up. The world was dark, but a

faint light spilled out from the bathroom. I could hear someone

reciting English words - it was Jung-hoon, our neighbor. He studies

so hard that he even uses his bathroom time to study! Watching him

made me think that if I also studied that hard, [Jung-hoon] brother’s

dream of becoming president might really come true.

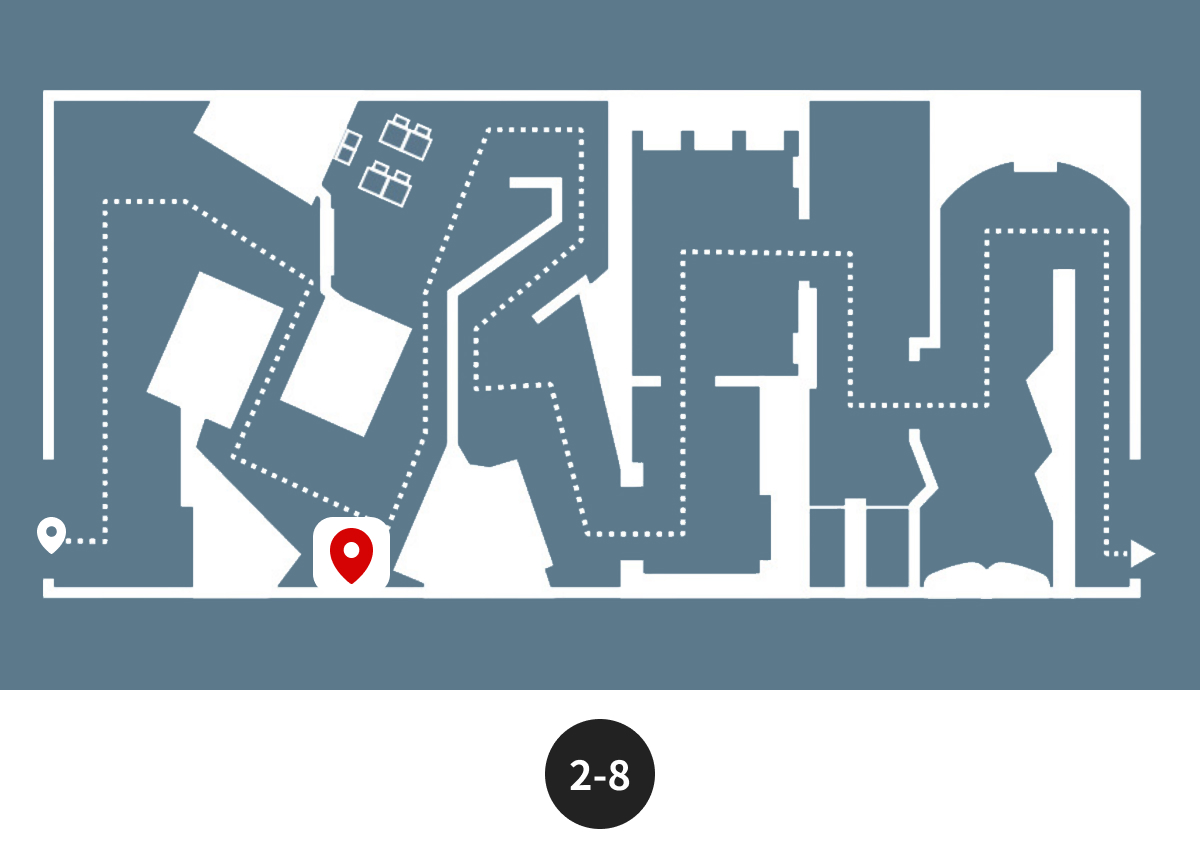

2-8 철수의 일기 Chulsoo’s Diary

Friday, May 30, 1952

If money could fall from the sky

On the way home from tent school, there’s a communal well where

the neighborhood ladies gather. They talk about things like, “That

college student teaches really well,” or “We have to pay this much

for lessons again.” While fetching water with sister, mother

sighed as she listened to them. Seeing her made my heart ache and

sink. Thinking of how hard father and mother work, I promised

myself I would study even harder.

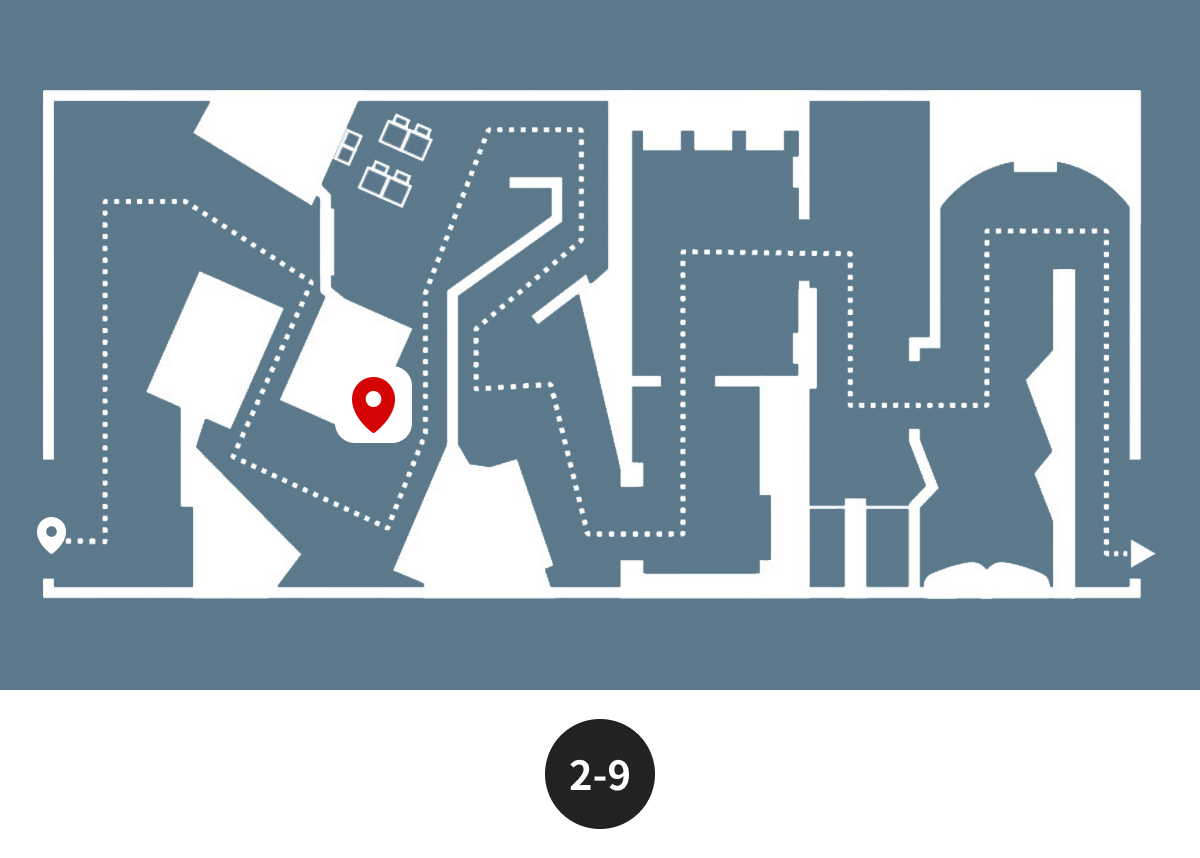

2-9 철수의 일기 Chulsoo’s Diary

Thursday, July 10, 1952

My heart pounds with excitement

Since last week, a college student has been coming to Jung-hoon’s

house. He’s on vacation and visits our hillside neighborhood to help

everyone study. Because of him, our whole neighborhood has come

alive-filled with the sound of children reciting multiplication tables in

the morning and the soft scratching of pencils from older brothers

and sisters studying in the afternoon.

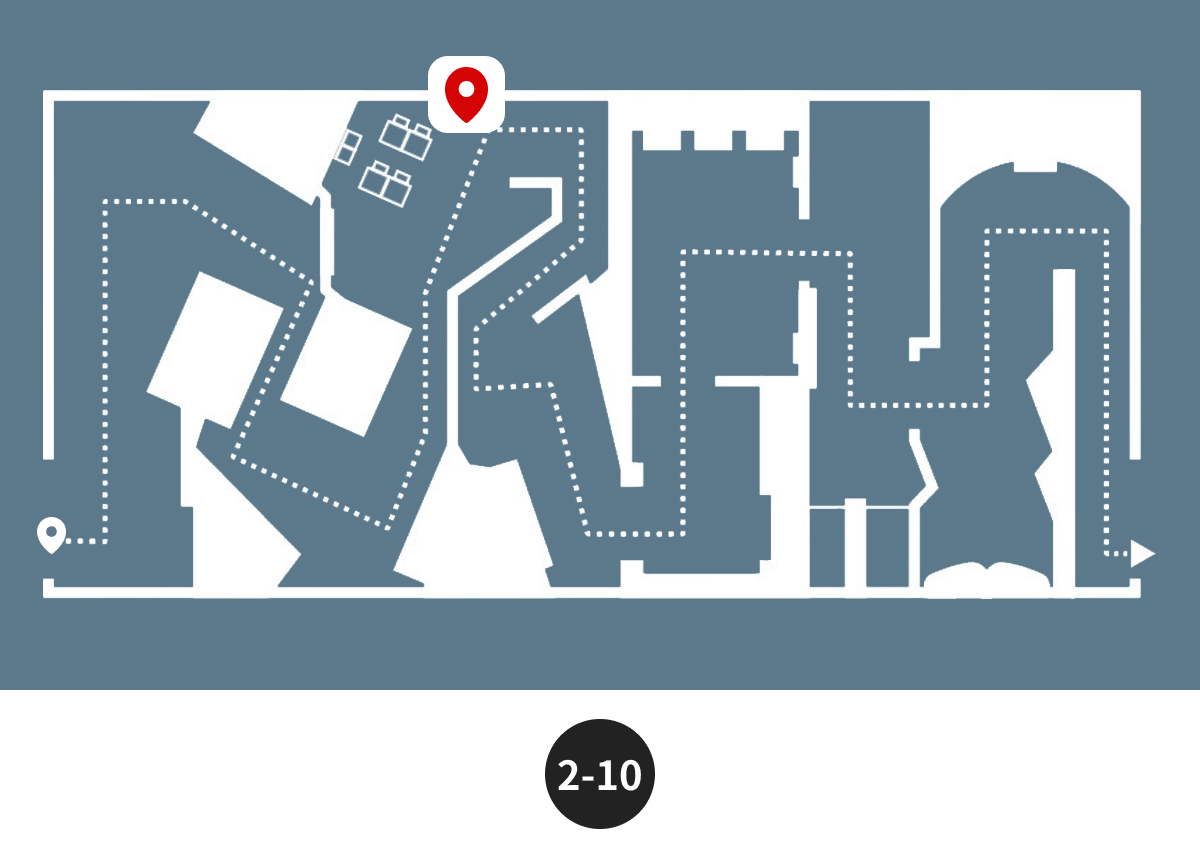

2-10 철수의 일기 Chulsoo’s Diary

Wednesday, September 3, 1952

The warmest day is when everyone’s hearts come together

The friends I met at the refugee school came from all over - North

Korea, Chungcheong, Gyeongsang, and Jeolla. We often struggled to

understand one another’s dialects, so the teacher grouped students

by region. As more children arrived, some couldn’t fit inside the

classrooms, so local adults helped build a new school. The children

and older sisters [older female neighborhood kids] dug stones, the

older brothers [older male neighborhood children] built huts, and the

teachers and villagers even brought military tents from the U.S.

army base. Now, we’re learning reading and math in the school that

we built with our own hands, and someday, we’ll study history and

foreign languages too.

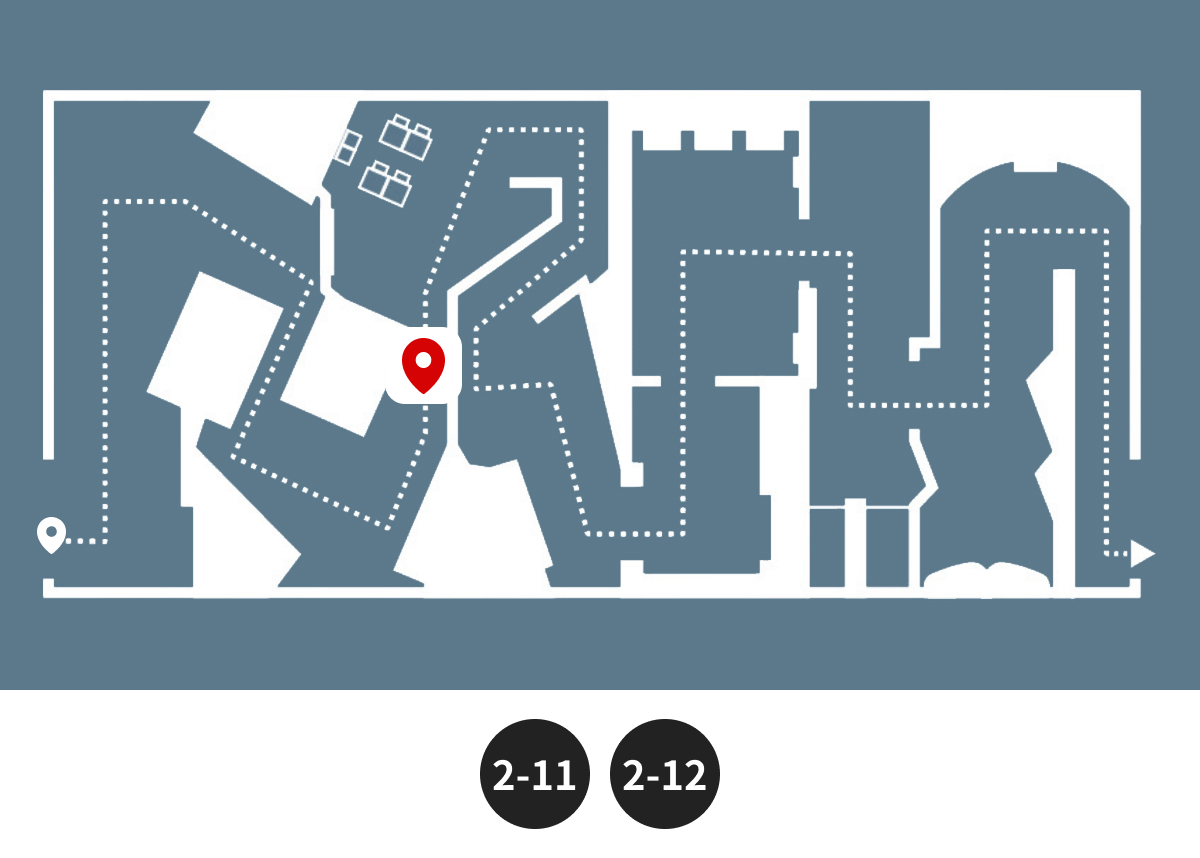

2-11 전시학생증 1953년 Wartime Student ID 1953, donated by Cho Seok-jong (조석종)

This is the front and back of a wartime student ID card issued in

April 1953 to a student in the architecture department of Gwangseong

Technical High School (today’s Gyeongseong Electronics High School).

The wartime student ID card was a special form of identification issued

during the Korean War and reveals the difficult circumstances of the

period.

It certified that the holder was a student, allowing him to continue

studying without being conscripted. It was also required when police

or soldiers checked identification. This was especially important in

Busan, the provisional capital, where many students had fled from

regions across the country. The card is a historical artifact that

demonstrates the determination to continue education even amid the

hardships of war.

2-12 4285년도 전시 국가 시험준비 표준수련장 1951년

Standard Workbook

This is a workbook for middle school entrance examination preparation,

compiled by the Workbook Compilation Committee. At the time, each

school’s principal administered its entrance examination, which led to

widespread admission irregularities.

This workbook for preparing the middle school entrance examination

was compiled by the Workbook Compilation Committee. At the time,

each school principal was responsible for administering that school’s

entrance examination, which led to widespread admission irregularities.

As a result, beginning in 1951, a national middle school entrance

examination administered by the government was implemented for

three years. To prepare for this exam, workbook-style study books

began to appear. These workbooks followed formats commonly used

in the United States, which oversaw Korean education during the

Korean War.

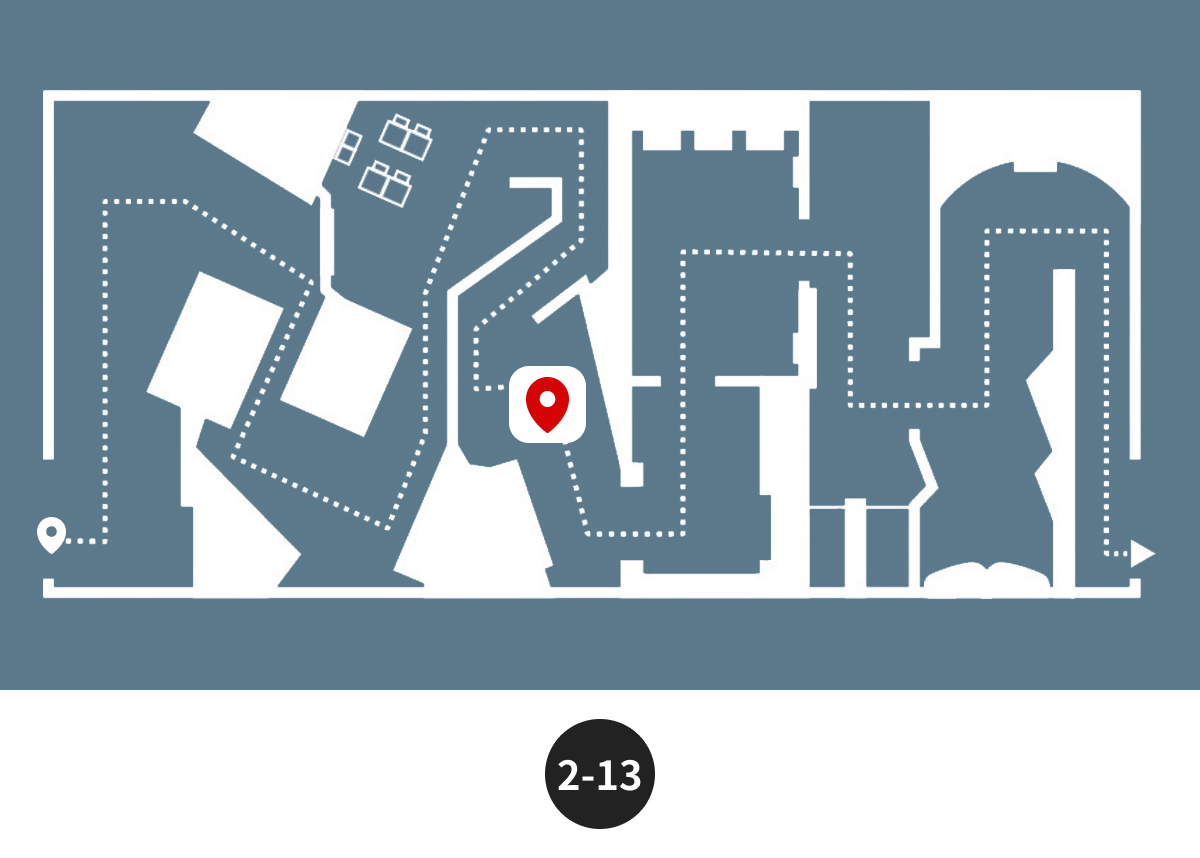

2-13 Soejeon Hospital, a School-Turned Hospital

During the Korean War, schools in Busan were transformed/adapted

to meet the needs of the time/times.

They served as hospitals, military facilities, and shelters for refugees.

Classrooms became wards for the wounded, playgrounds turned into

temporary residential areas for refugees, and the places where students

learned became life-saving spaces in the midst of the war. Among

these facilities, Soejeon Hospital (Swedish Red Cross Hospital), the first

Western-style hospital in Busan, was built on the site of the former

Busan Commercial High School.

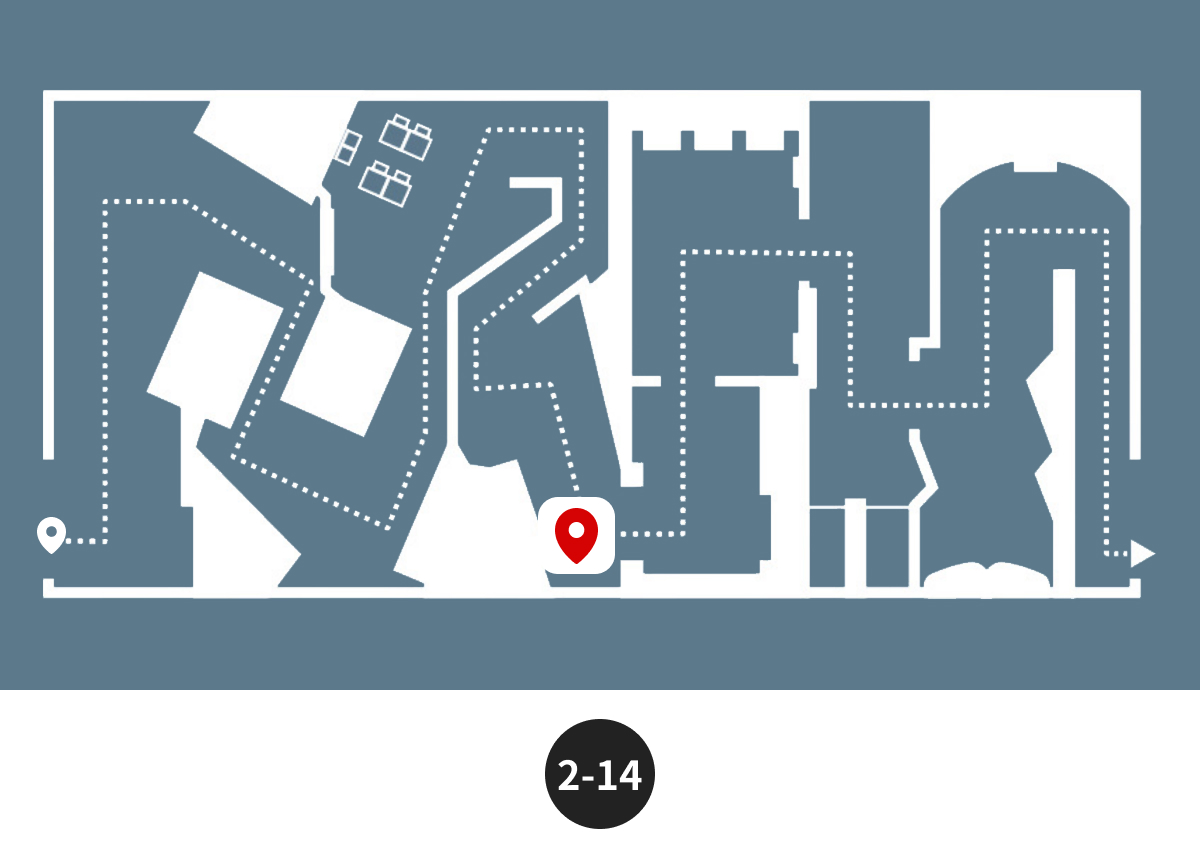

2-14 철수의 일기 Chulsoo’s Diary

Wednesday, October 15, 1952

Countless stars have settled and shine

I became friends with a boy who shines shoes around the stalls at

the international market. He told me he lost his patents while fleeing

to Busan during the war, and that he learned to shine shoes, after

vowing to live like his always-diligent parents. He kept a book in his

shoe-shine box and studied whenever he could. Seeing him like that

was truly admirable. Although our country is going through a war

now, the war has not taken away our hope. I think that if he and I

don’t give up and keep doing our best for a brighter future, we can

become hope for the Republic of Korea.

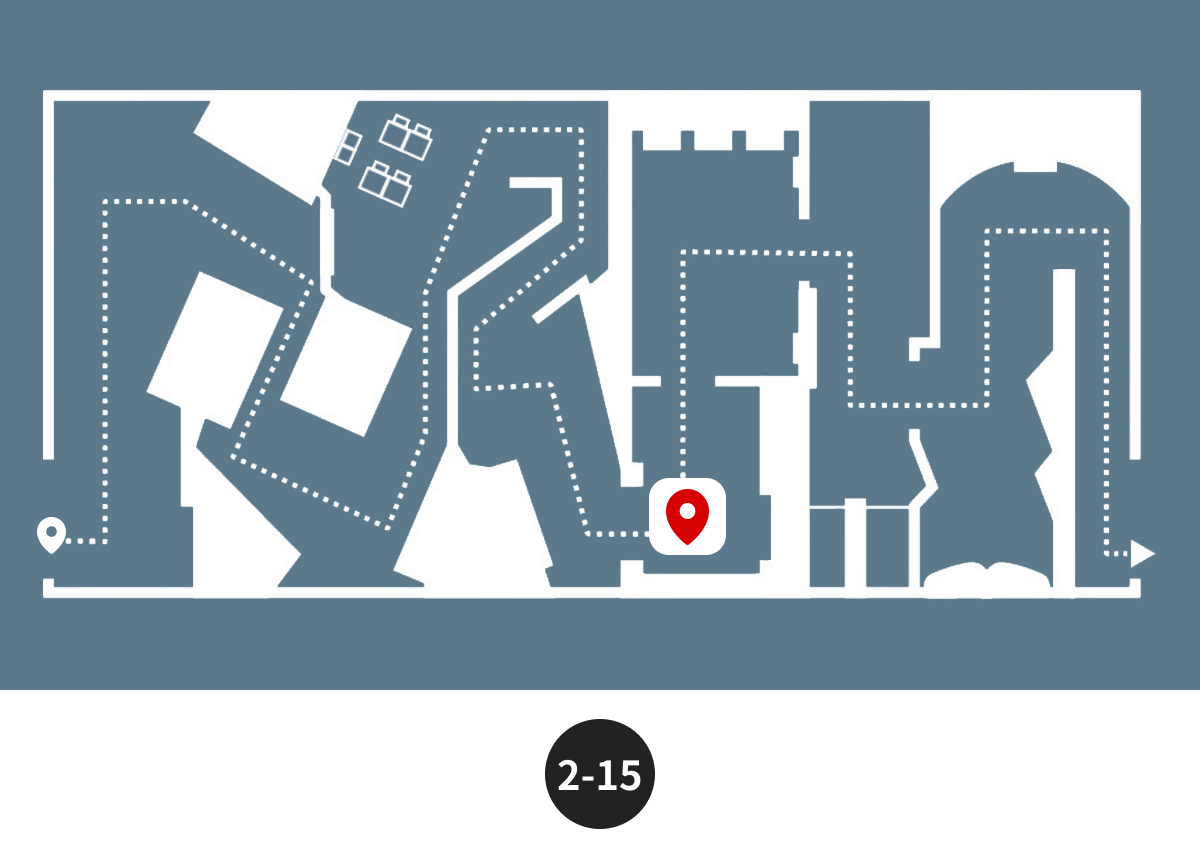

2-15 Leading Korea’s industrialization

In the aftermath of the Korean War, a new national curriculum was

introduced, and elementary, middle, and high schools were steadily

expanded. Thus, creating an environment in which many more students

could receive an education.

From the 1960s onward, education in Busan emphasized science and

technology and introduced vocational programs aligned with industrial

needs to help students develop practical skills. These changes in

education, together with Busan’s industrial growth, greatly contributed

to the development of the local community and the nation

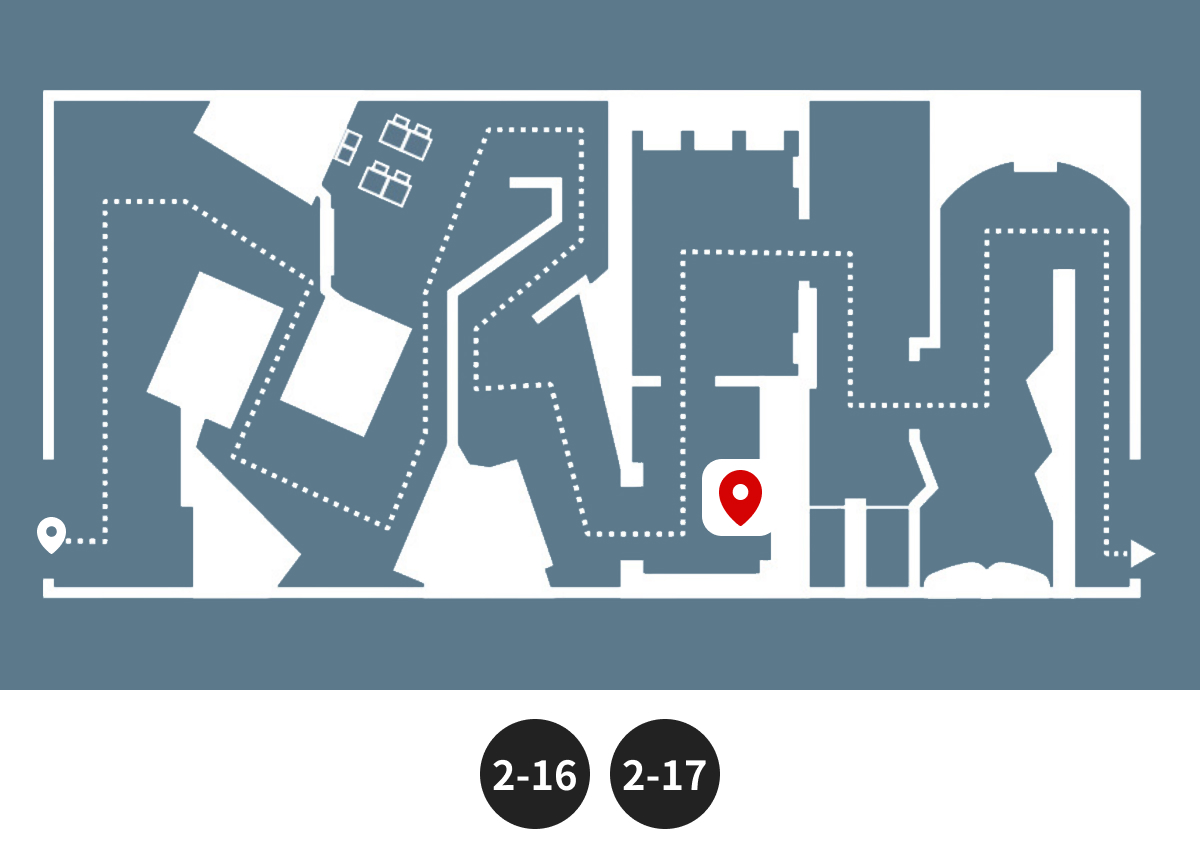

2-16 Student Democratization Movement in Busan

In Busan in the 1960s, high school students led a series of large and

small protests against fraudulent elections and authoritarian rule.

With most of the high school students in Busan participating, the

demonstrations developed into coordinated, citywide actions, and in

some cases middle school students also took part.

As university students and ordinary citizens joined the protests, they

gradually grew into a broader civic uprising. This collective resistance

ultimately led to the resignation of President Syngman Rhee (이승만),

safeguarding Korean democracy through the power of civic action.

However, many people were injured or lost their lives in the process.

In Busan, in particular, a student protester named Kang Su-yeong

(강수영) was shot and killed. The spirit of the student democratization

movement in Busan later continued in the Buma Democratic Uprising

and the June Democratic Uprising.

2-17 반공독본 1954년 Anti-Communist Reader 1954

In July 1953, with the signing of the Korean War Armistice Agreement,

Korea was divided into North and South along the 38th parallel. The

government then made the unification of the people’s ideology a key

task, and materials for ideological education, such as the

Anti-Communist Reader, were produced.

In the wake of division and war, anti-communist education was

introduced in schools to protect the nation and secure peace. Classes

used stories and illustrations to make the educational content easier for

elementary school students to understand

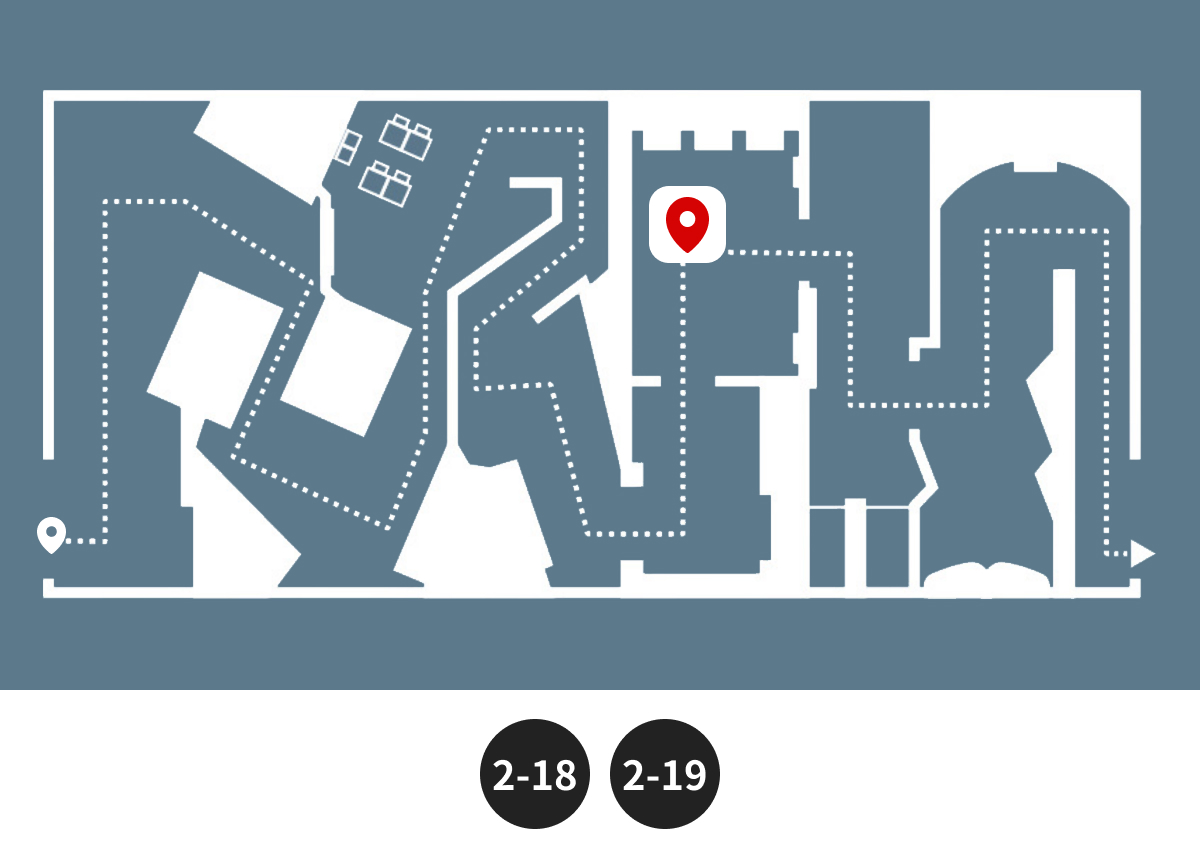

2-18 Military training (교련, gyoryeon) was a form of military drill

conducted for high school and university students. It emphasized the importance

of national security and aimed to develop the knowledge and skills

needed to protect students’ safety in the face of disasters and national

threats.

This type of education existed before the liberation of Korea, but it

became more active after the Korean War and was introduced as a

compulsory subject in vocational high schools under the Second

National Curriculum. It continued until 1993, when it was abolished

as a required subject.

2-19 Industrialization and Education in Busan

From the 1960s onward, Busan developed into an industrial city and a major hub connecting the light industrial zones and the heavy chemical industrial zones along the southern and eastern coasts. As industrialization progressed, vocational education to support economic development was increasingly emphasized. As a result, the number of vocational and technical high schools grew, and technical education came to play an even more important role

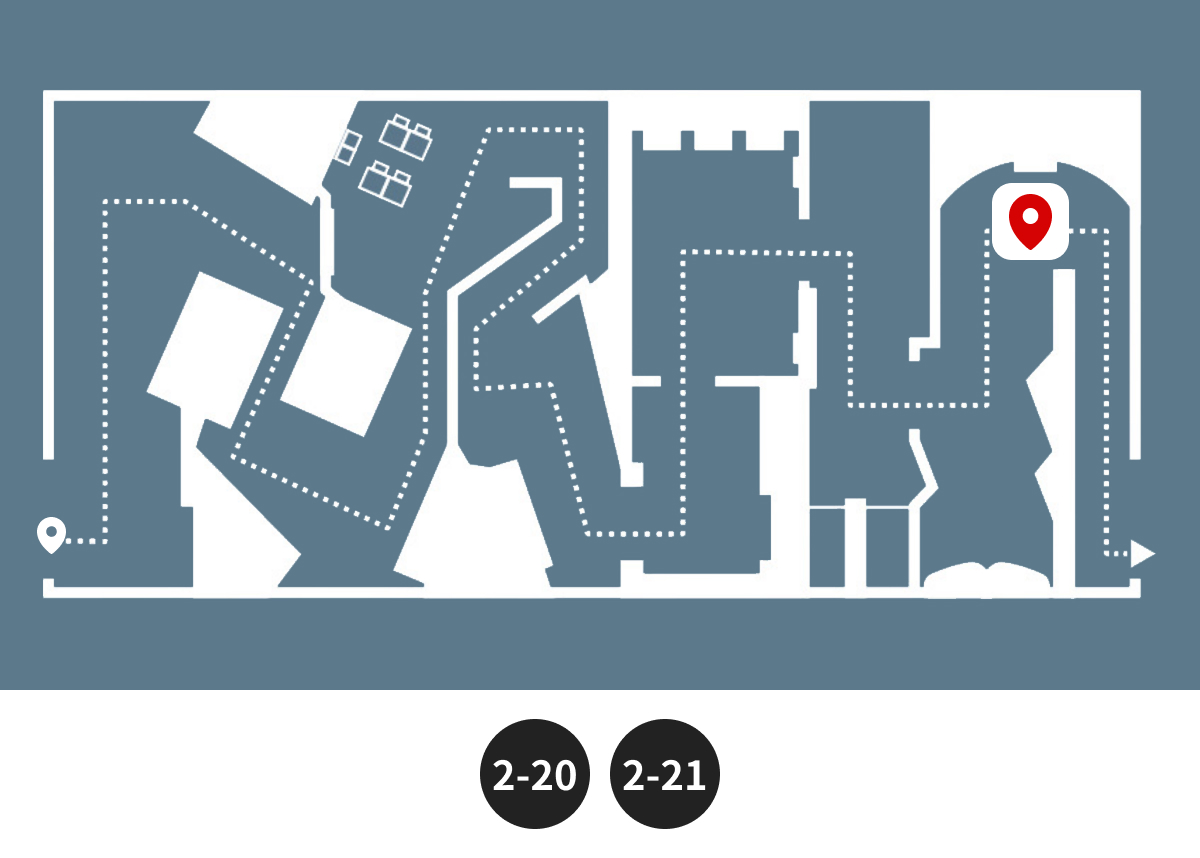

2-20 Education Autonomy in Busan

Since the launch of local autonomy in 1990, the Busan Metropolitan Office of Education has created curricula and textbooks tailored to the city’s distinct character. By weaving Busan’s culture and identity into lessons, the city provides education that enhances students’ learning and strengthens their sense of connection to their region

2-21 Busan’s Regionalized Textbooks & the Evolution of Busan Education

Busan’s regionalized textbooks began with ‘Life in Busan,’ a fourth-grade social studies book, introducing students to their city. ‘Rediscovering Busan,’ now used in middle schools, explores local characteristics and potential to inspire future growth. Additional publications, ‘A.I., Tell Me About Busan’ and ‘Environment and Future of Busan’ expand learning to include artificial intelligence, regional culture, and social challenges. The Busan Metropolitan Office of Education also promotes learner-centered classrooms through cutting-edge edutech tools such as AI, AR, VR, the metaverse, and digital textbooks, while supporting digital experience programs and student clubs that help cultivate the skills needed for the future.

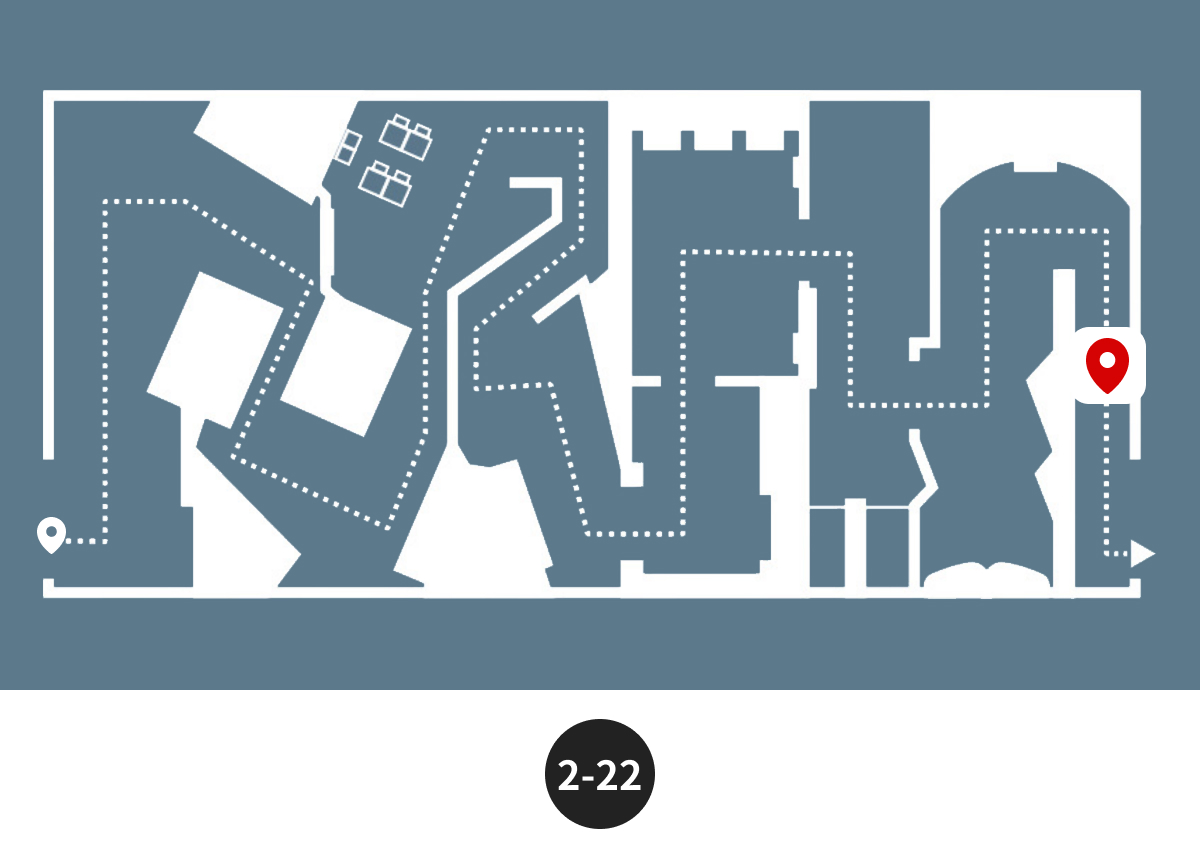

2-22 표준화 국어읽기 음반 1960-70년대로 추정, 3M교육자료사 Standardized Korean Language Reading Record 1960s-70s, 3M Educational Materials [training and safety materials]

This audio-visual teaching material was produced to help first-grade students in national citizens’ schools systematically develop their reading skills by listening and reading along. The first track introduces what students will learn through the textbook.

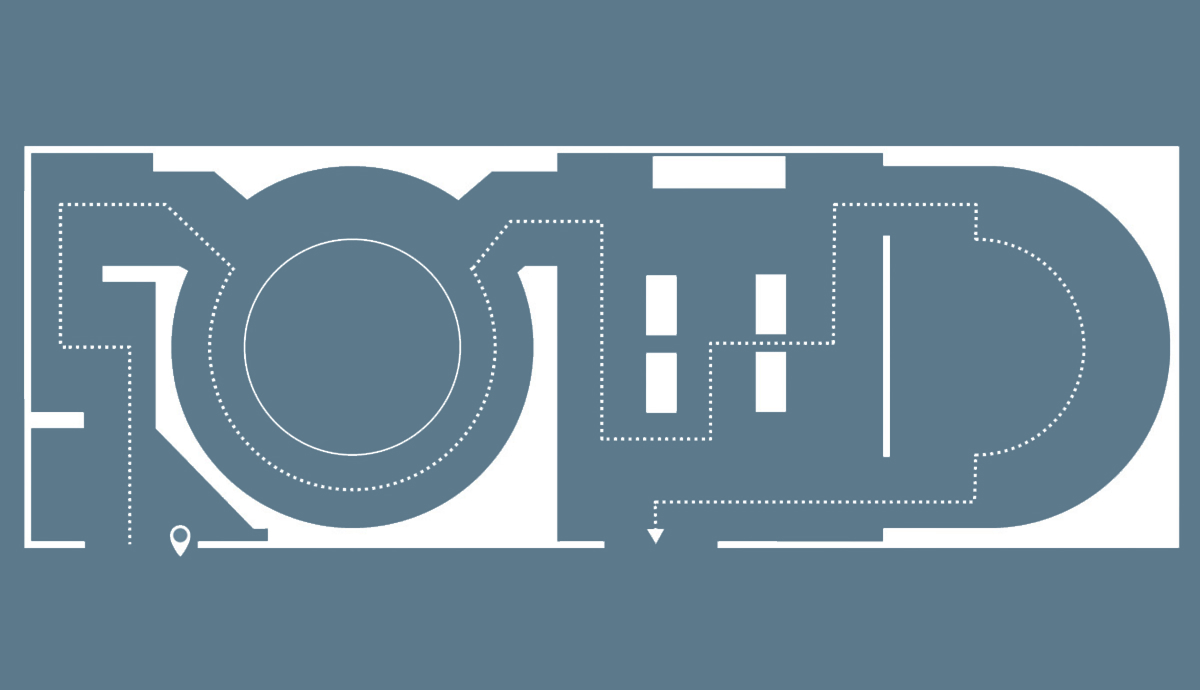

Are you learning?

This space delves into the essence and value of learning through immersive videos that combine realistic images and interactive shadow effects, offering a fresh perspective on what it means to learn. In Permanent Exhibition Room 1 and 2, you can witness the ever-changing nature of education as it adapts to the flow of history and the ever-changing environment. In contrast, Permanent Exhibition Room 3 offers a glimpse into the timeless essence of education, unaffected by the passage of time or environmental changes.